If Judge Charles Breyer’s order reads like carefully woven case law missing the point of the exercise, that’s because it is.

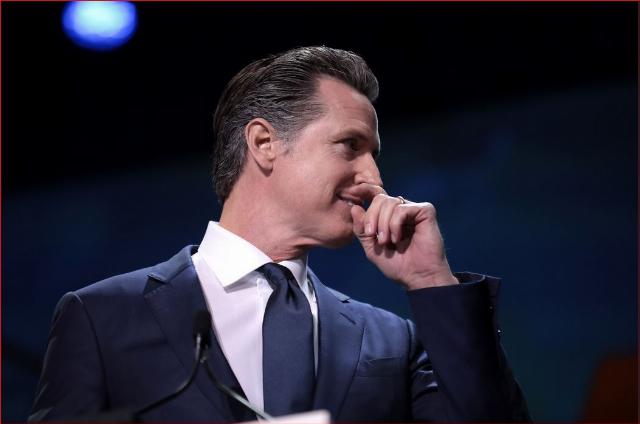

His injunction requiring President Trump to return control of the California National Guard to Governor Gavin Newsom isn’t just wrong—it’s historically uninformed, legally unsound, and politically transparent.

Judge Breyer claims the federalization violated the Tenth Amendment, accusing Trump of commandeering California’s Guard.

That’s an astonishing claim—especially coming from a progressive legal movement that had little concern for the Tenth Amendment when President Biden imposed vaccine mandates, micromanaged school funding, or sued Texas for trying to defend its border.

For the left, the Tenth Amendment is a relic—until a Republican president sits in the Oval Office.

Their on-again, off-again affair with states’ rights returns with antebellum vengeance—draped in the language of federalism, weaponized to obstruct federal authority, and selectively revived whenever the White House changes hands.

But their newly rediscovered affinity for these legal precepts is hardly grounded in principle. It’s partisan opportunism with a skinny-tie bow wrapped around it.

The abiding principle during this administration—for the left—is simple: Stop Trump at all costs.

Let’s review what the Constitution and the law actually demand.

Article II, Section 2 of the United States Constitution designates the president as “Commander in Chief of the Army and Navy of the United States, and of the Militia of the several States, when called into the actual Service of the United States.” In this context, the militia is the California State National Guard.

When the president lawfully federalizes a National Guard unit—whether under Title 10 or the Insurrection Act—command transfers fully and lawfully to the president. 10 U.S.C. § 12406 leaves no ambiguity: in cases of invasion, insurrection, or obstruction of federal law, the president may call the Guard into federal service.

That authority is not contingent on gubernatorial consent. It is not subject to judicial review of the exercise of this discretion. It is a core constitutional power—vested in the executive by statute and by the Framers themselves.

These laws have been invoked time and again throughout American history. In each case, the federal government did what the Constitution compels: it defended order, enforced federal law, and protected the union.

Simply put, the courts—including the federal outpost in San Francisco—lack the authority to second-guess the Commander in Chief’s lawful determination under the authority vested in him by statute and the Constitution. To hold otherwise is without precedent, without merit, and cannot be allowed to stand.

This is especially true when the governor of a state—alongside the municipal leaders of its largest cities—has openly declared opposition to federal immigration enforcement, fanned the flames of manufactured outrage, and presided over an environment where violence and widespread property destruction have followed.

In California’s case, the governor seemed more interested in trolling federal officials on social media than in extinguishing the hooliganism within his borders.

Invocation of federalism and the Tenth Amendment to block the federal government from protecting its agents and enforcing its laws is not just bad constitutional law—it is a mockery of constitutional governance. The Constitution is not a suicide pact.

The president’s authority in these matters is nearly as old as the Republic itself.

Shortly after ratification of the Constitution, George Washington marched at the head of 12,950 troops—mostly federalized state militias—during the Whiskey Rebellion of 1794 to enforce a federal tax on, wait for it, whiskey.

Washington donned his old general’s uniform, strapped on his saber, mounted his horse, and prepared to lead the troops himself to ensure the law was enforced.

That wasn’t authoritarianism. It was constitutional duty in action.

And Chief Justice John Marshall wouldn’t have dared to stand in the way of President Washington.

Fast forward to 1957: When Arkansas Governor Orval Faubus deployed his state’s National Guard to block black students from entering Little Rock Central High School, President Eisenhower federalized the Guard, removed Faubus from command, and sent in the 101st Airborne to enforce federally mandated desegregation.

In 1992, as Los Angeles erupted after the Rodney King verdict, President George H.W. Bush federalized the California Guard and deployed the Marines to restore order.

Now compare: in 2025, foreign nationals and others in Los Angeles assaulted ICE officers, vandalized federal buildings, blocked highways, and waved the flags of other nations.

When the president stepped in to restore order, Newsom ran to court, where Judge Breyer issued an order that was as erroneous as it was provocative.

Judge Breyer objects that the president didn’t sufficiently route his federalization order “through the governor” as required by § 12406. Why? Although the orders were labeled “Through: The Governor of California,” they weren’t hand-delivered to Gavin Newsom himself.

But the law doesn’t demand gubernatorial sign-off. It requires the order to be issued through the governor—not by the governor.

In practice, that function was fulfilled: California’s adjutant general, the state’s military executive who acts “in the name of the Governor,” received and implemented the orders, as per California law.

The idea that a federal military directive becomes void unless ceremonially routed through a hostile governor—who has publicly vowed to obstruct it—is bureaucratic nonsense. Breyer’s objection elevates optics over substance—and ministerial form over constitutional command.

This is not the first time Congress has required a courtesy notice to state executives. But it is the first time a federal court has pretended that a statutory formality—meant to notify, not empower—permits a governor to override the president’s constitutional role as commander-in-chief.

Judge Breyer even wrung his hands over photographs showing armed National Guard troops standing near ICE agents during arrests—though he conceded the Guard had not made arrests, used force, or conducted searches.

Apparently, under his logic, mere proximity to immigration enforcement is now grounds for constitutional alarm. Must the Guard be stationed across town to avoid offending progressive sensibilities? Or would a different ZIP code suffice?

With all due respect, Judge Breyer, that’s the point. The Guard is there to protect sworn federal officers from violent hooligans—and that mission necessarily requires them to be close enough to do the job.

Judge Breyer didn’t reach the Posse Comitatus Act (PCA) as a basis for his ruling. The plaintiffs raised it as a third ultra vires argument, but the court reserved it for “future consideration.”

It should have been dispensed with altogether—because the PCA doesn’t apply here. It’s a red herring, and everyone should know it. The Act codified at 18 U.S.C. § 1385, contains an express carve-out for circumstances “authorized by the Constitution or Act of Congress.”

That’s precisely what this is. When the president deploys National Guard troops—under statutory and constitutional authority—to protect federal officers and property from violent mobs, that’s not a violation of the PCA. It’s the lawful exercise of executive power.

The Ninth Circuit stayed Judge Breyer’s order with disarming quickness—a rebuke as swift as it was warranted.

What the left fears isn’t the misuse of military power. It’s that the Supreme Court might finally reaffirm what the Constitution has said all along: that the president—not a governor, not a riot, not a robe—holds the final authority to enforce federal law.

And that authority reaches its constitutional zenith when the president defends the nation’s sovereignty and deploys military personnel to enforce federal law—especially when a state government is actively obstructing it.

Perhaps it’s time California got serious about the borders that matter.

The Golden State has vanished into a myopic wonderland—hardly wonderful for its law-abiding citizens or the other states of the Union. Its leaders seem more concerned about a tomato crossing the Nevada line than about gang-bangers, cartel traffickers, fentanyl peddlers, and human smugglers flooding across the southern border.

Through the looking glass, indeed.

There are terms for what Newsom is attempting to do.

Despite the progressive left’s best efforts at camouflage, this isn’t federalism. It isn’t constitutionalism.

It’s sedition. It’s insurrection. It’s nullification.

It’s John C. Calhoun redux—with a hairstylist on retainer.

The courts must quash this order forthwith.

Charlton Allen is an attorney and former chief executive officer and chief judicial officer of the North Carolina Industrial Commission. He is founder of the Madison Center for Law & Liberty, Inc., editor of The American Salient, and host of the Modern Federalist podcast. His commentary has been featured in American Thinker and linked across multiple RealClear platforms, including RealClearPolitics, RealClearWorld, RealClearDefense, RealClearHistory, and RealClearPolicy. X: @CharltonAllenNC

Image: Gage Skidmore, CC BY-SA 2.0, via Flickr, unaltered.

Source link