Many people are justifiably tired of failed overseas wars, fought by men who were lions but led by donkeys, in which defeat was consistently wrested from the jaws of victory. These conflicts led to trillions of dollars in wasted money, over 8,000 lost American lives, and entire regions upended and sent into the chaos, which has fueled the current immigration crisis in Europe and, partially, the United States.

It can be tempting, with the current “Specter of the Global War on Terror” under which we live, to be cynical: “No more overseas bases” and cries to eliminate our military presence in over a hundred countries can be a seductive reaction to the abject failure of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. I served in both conflicts as a soldier in the United States Army, and the day Kabul fell was similar to how many Vietnam veterans felt when they witnessed the fall of Saigon.

International Strategy

The economic lifeblood of a nation like the United States in 2024 is international trade — both the import and export of goods. To start: It is an abject crime against the national security of our nation that we have exported our manufacturing jobs overseas since the 1970s. Although this is a key factor in many of the problems affecting the U.S. today (see the cultural decline of the Rust Belt), it is not the most important theme in this article.

Even if the United States can manage to return manufacturing jobs to the USA, we will still need to safely and securely export those manufactured goods to other nations. And unless we are exporting to Mexico and Canada (and in some cases, even then), those goods must be transported using naval ships.

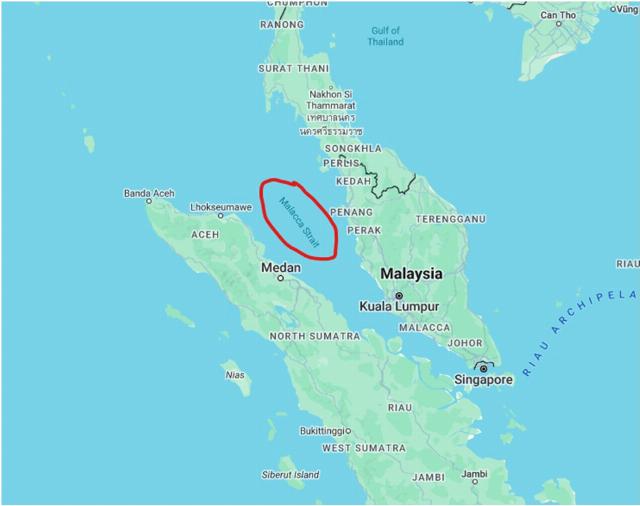

There are four key “chokepoints” to global trade: the Strait of Malacca in Asia; the Panama Canal in Central America; the Suez Canal in Africa and the Middle East; and the Strait of Gibraltar, which is the gate between the Atlantic and Mediterranean. Many billions of dollars in U.S. overseas trade traverse all of these, and there are many other sea lanes important to U.S. trade that I do not have the space to elaborate on (Hormuz being one of them).

Although one might ask, “Why not just go around them?,” it is important to remember that operating a ship costs fuel, pay and medical insurance for the crew, and maintenance. Without the use of these sea lanes, the price of international trade would go up significantly.

The Strait of Malacca is located between Malaysia and Indonesia. Twenty-five percent of all traded goods in the world traverse this strait. It is a key link between the U.S. and Europe and Asia, and even if we managed to balance the books on imports and exports, ships carrying American goods would still need to utilize this sea lane.

The Suez Canal and Gibraltar control access to the Mediterranean. Without securing these sea lanes, ships traveling from the Atlantic to the Indian Ocean (and thus, most of Asia) would have to travel around most of Africa. This would add about 4,800 nautical miles to the journey, or approximately ten days, depending on the speed and weather conditions.

Finally, the Panama Canal provides a vital link between the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. Without it, ships would need to traverse an additional 8,800 nautical miles, or about 18 days, to go from Atlantic to Pacific. In addition, there is the risk of traveling around Cape Horn, an area known for its bad weather, which is still a danger even to modern ships.

The consequence of losing access to these vital shipping lanes would be increased costs in fuel, crew pay, insurance, and danger to the ships and seamen themselves. When the Suez Canal was blocked in 2021, it cost $400 million per hour in expenses and trade lost.

Military Strategy

To secure our shipping — and Trump will hopefully get the ball rolling on exporting more than we import — the ships need to be protected from pirates and hostile nations. Pirates must be confronted, as Thomas Jefferson did when he sent the U.S. Marines and Navy to confront the Tripolitan Pirates during the Barbary Pirate Wars (“to the shores of Tripoli”). Further, hostile nations must be deterred from starting wars or attacking U.S. shipping: the entire Battle of the Atlantic against German U-Boats in World War II is a prime example of this. The United States Navy was fighting German U-Boats before December 7, 1941, to protect our international trade from being sunk by the Nazis.

Unlike the Age of Sail, when Jefferson could send a few small warships from America to North Africa directly, a modern Navy requires immense amounts of supply: food, fuel, replacement parts, and ammunition must all be resupplied to a warship at sea. Even our mighty nuclear-powered aircraft carriers must be protected by destroyers that run on oil, and the airplanes launched from their flight decks consume an immense amount of petrochemicals.

All these supplies must be stored in naval bases throughout the globe. It is simply not practical to have our ships use only U.S. ports (the mainland, Hawaii, Alaska, and various other territories such as Guam and the Marianas). Our ships protecting our trade in the Mediterranean must be supplied with fuel and munitions from bases in Italy, and sometimes even be refueled in Middle Eastern or North African ports.

As World War II ushered in the end of the battleship, naval bases must also have air bases. And these bases must be protected by American soldiers and Marines. Modern military aircraft are just as demanding on fuel, replacement parts, and ammunition as warships, which must all be delivered by sea (and sometimes by air in an emergency), which can happen only if the sea lanes are secure.

The logistics required to protect our overseas trade is immense: depending on the operational tempo, a single destroyer consumes 100–200 tons of supplies per day. It is simply impractical to supply this using sealift capability from U.S. mainland ports for any significant length of time.

To maintain these bases, which supply the ships and aircraft that protect our trade, the United States must get the host nation to agree to allow us to build a military base there. The logistical requirements to protect our trade are immense, and you can’t win tactical battles or maintain an effective deterrent to avoid war without a secure logistical supply chain.

Geopolitics and Strategy

“Why are we giving billions of dollars to nation X when we have problems at home?” is a question often asked in American policy circles with varying degrees of legitimacy. To the average American suffering under crushing inflation or living in poverty in the Rust Belt, it can be easy to ask, “Why don’t we spend that money here?”

There is no doubt that the United States should increase its investment in itself, infrastructure and manufacturing being two high priorities. Our garbage elites have often shipped jobs overseas just to make a dishonest buck or given too much of our foreign aid money to cronies, who then kick some of it back (looking at you, Hunter Biden, and your pals in Ukraine).

In geopolitics, money is a weapon. U.S. foreign policy aid, which can range from the direct delivery of goods or military equipment to direct cash transfers to the U.S. underwriting loans for our allies, is part of maintaining the political relationships that allow us to have the overseas bases we need to secure our trade. Even if President Trump were to totally reverse the trade imbalance by resurrecting American manufacturing in February 2025, we would still need to protect that trade using our military. To do that, we need overseas bases, which rely on international alliances, many of which are supported by the U.S. giving aid in the forms mentioned above.

Without going into the details of international relations, maintaining international alliances and treaties is a highly complex process that involves a lot of carrot and stick. Sometimes we must threaten. More often, we must cajole, bribe, assist, or take other action.

A revolution in Cairo would affect people in Ohio by potentially cutting off the Suez Canal, raising the price of imported/exported goods, and sending our supply chains for basic consumer goods, food, or natural resources (being imported or exported) into chaos.

Yes, Things Go Wrong

It is not my intention to anger readers, especially those with libertarian leanings. Things do often go wrong when executing our foreign policy to protect the U.S. economy by protecting our international trade. Corrupt people, like most of our current leaders and elites, get us into wars with no serious plan to win them. The elites and leaders will often lie, steal, and cheat to enrich themselves at the cost of average Americans, most of whom do not spend hours poring over books on international trade, strategy, and diplomacy. (For that matter, neither do the leaders and elites.)

Even if President Trump and subsequent leaders manage to fix many of the problems mentioned in this article, the United States of America will still need to protect its exports as well as the import of resources that we do not have. To do this, we will need a robust military that is capable of both confronting and deterring any threat that may come about. This robust military can be supported only by bases in overseas countries, which requires investment in international strategy.

To Make America Great Again, we need to protect the economic lifeblood of the nation. This article is but a brief overview of how we protect U.S. international trade, which was a substantial portion of our economy even when we were exporting more than we imported and the Rust Belt factories were bringing U.S.-made consumer goods to the market. As we look to the future, we must not look to slogans like “no more overseas bases.” We must carefully consider our international strategy and how it will affect the average American.

Source link