China Turns to ‘Marxist Population Theory’ to Fix Birth Rate Collapse

STR/AFP/Getty Images

STR/AFP/Getty Images

The National Committee of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC), a top advisory committee to the Chinese Communist regime, met on Saturday to discuss the ongoing population crisis.

The chairman of the committee, Wang Huning, advised using “Marxist Population Theory” to “analyze the new population trends, characteristics, and problems that China faces.”

The state-run Global Times' account of Saturday’s conference did not explain Marxist Population Theory in detail or explain how Wang wanted to use it to increase the national population. Marxism excels at killing people, using a variety of methods ranging from war and political executions to enforced starvation, but its track record for healthy population growth is more dubious.

Karl Marx’s “population theory” largely consisted of believing that more workers producing more output was good, provided they did not starve — which, as mentioned, is one of the things Marxism has trouble with. One of his complaints about capitalism was that he felt it would lead to overpopulation because low wages and rapacious capitalist demands for labor gave workers no incentive to stop having babies.

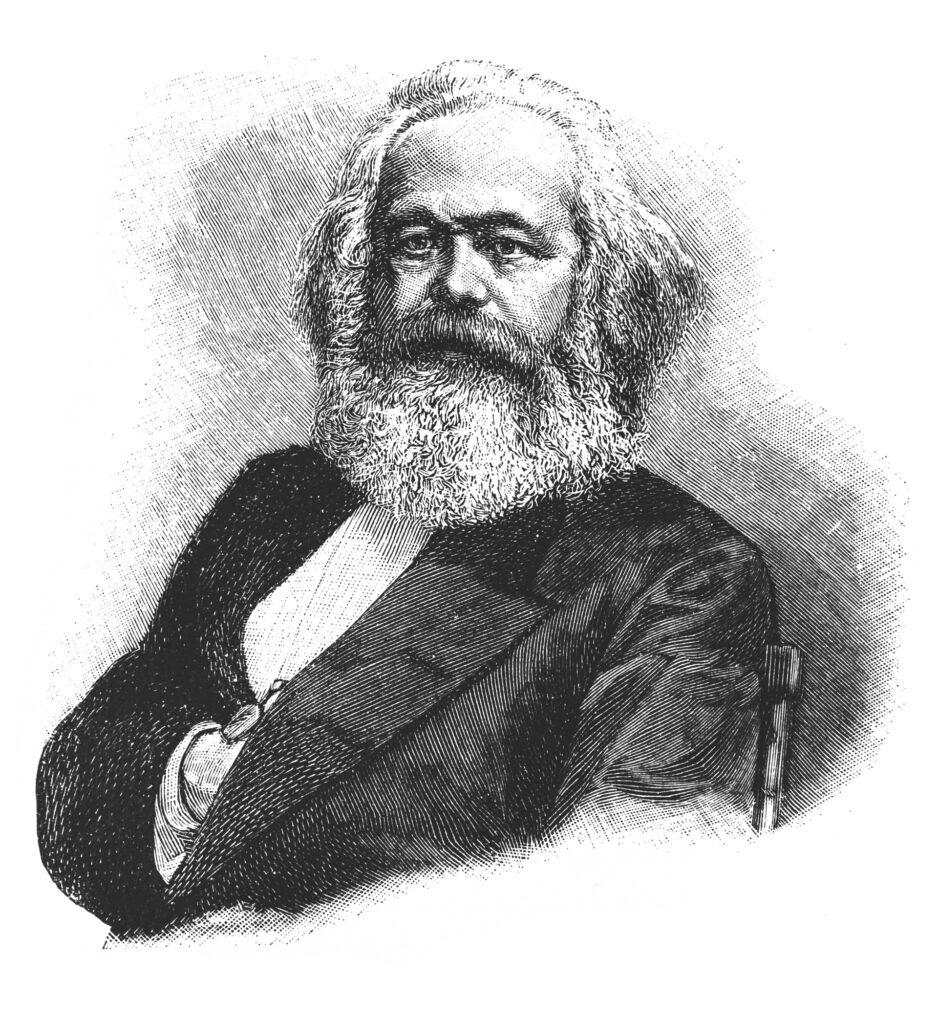

Illustration of Karl Marx (1818-1883)

Marx thought China was overpopulated in his day, leading to Maoists deciding to cull the population with harsh limits on family size, compulsory sterilization, and forced abortion. A big part of the current crisis is due to how brutally effective the One Child Policy was.

The few details the Global Times did provide at the conference made it sound like the hundred-member committee did little but recommend more of the same tactics China is already using, without much success, to arrest its population freefall:

Chinese Vice Premier Liu Guozhong, a member of the Political Bureau of the CPC Central Committee, stressed that efforts should be made to improve targeted and effective measures of fertility support, and reduce the costs of fertility, child-rearing, and education.

“It is necessary to accelerate the improvement of population governance capacity and standards, coordinate and provide services for the elderly and children, promote the construction of a fertility-friendly society, and accelerate the shaping of a high-quality population development trend with excellent quality, sufficient quantity, optimized structure, and reasonable distribution, in order to support China's modernization through high-quality population development,” Liu said, as quoted by the People's Daily.

CPPCC member and former family planning official Wang Peian told the Global Times the answer would involve some combination of “including increasing economic support, improving childcare services, optimizing time support, strengthening intergenerational care support, enhancing cultural guidance, and strengthening reproductive health services.”

China is increasing subsidies for children to incentivize new parents. Total one-time subsidy packages are more than $4,000 U.S. in some areas, a very high sum for Chinese workers. One village in the southern Guangdong province is offering extra subsidies for a second child and an even bigger reward for a third — a reasonable strategy given the importance of three-child families to population growth, but a striking turnaround from the One Child Policy and China’s slow, grudging abandonment of it.

This photo, taken on May 17, 2018, shows a poster in Chinese promoting in vitro fertilization displayed in the lobby of Piyavate Hospital in Bangkok (LILLIAN SUWANRUMPHA/AFP via Getty Images)

Guangdong actually has the highest fertility rate in China, possibly due to the bustling job market it enjoys as a major industrial hub, and it was ahead of the curve in providing incentives for childbirth. This is apparently leading national government planners to think their best bet for halting population decline is to recreate Guangdong’s policies and conditions in as many places as possible.

Wang Peian told the Global Times:

Less and less young people want to have children. This is due to a number of factors, including higher education which can impact plans to get married and have a family, the high cost of raising children in modern society and the weakening of traditional family culture. These trends have contributed to smaller family sizes and a shift toward delayed marriages and DINK (dual income, no kids) households.

Wang saw signs of optimism in a slight uptick in births over the past year:

In addition to people preferring to have a child during the Chinese Year of the Dragon, the phase-out of the COVID-19 pandemic, increase in the number of marriages, and optimization of fertility policies are also expected to have a positive influence on the birth rate.

Some of the factors Wang mentioned are ephemeral, like the pandemic and the Chinese Zodiac. Increasing childcare subsidies has not helped as much as anticipated, perhaps because the opportunity cost for young people — especially young women — of getting married and raising children at a young age is still too high for them to bear. It is hard to imagine a subsidy big enough to make nervous students in a shaky economy with a highly competitive job market decide to spend their twenties raising children.

Source link