© Harappa.comThe site of the dockyard at Lothal, Gujarat, during the Harappan or Indus Valley Civilisation.

This may now change as a new study by the Indian Institute of Technology-Gandhinagar (IITGn) has found fresh evidence that can confirm the dockyard's existence. This pioneering research reveals fresh insights into how the region's hydrography shaped ancient trade and cultural interactions.

Harappan civilization, also known as the Indus Valley Civilisation or Indus civilization, is the earliest known urban culture of the Indian subcontinent. The dates of the Civilisation appear to be about 2500-1700 BCE, though the southern sites may have lasted later into the 2nd millennium BCE. Among the world's three earliest civilizations — the other two are those of Mesopotamia and Egypt — the Indus Civilisation was the most extensive.

As an anomaly in the overall pattern of Harappan settlements, Lothal is situated in the southernmost part of this civilization. Around 2500 BCE, it is thought that indigenous groups of craftsmen and traders with strong ties to the Sindh and Kachchh regions started to occupy Lothal. The Harappans occupied Lothal over the course of the following two or three centuries, building a planned settlement with new industries and increased trade.

Also, Lothal is best known for its well-preserved brick dock and its warehouse, though the hypothesis that this structure served as a dockyard has been the subject of debate in the archaeological literature.

Artifacts of foreign origin found in Lothal confirm its intercultural trade relationships with other civilizations.

© Wikimedia CommonsThe site of the dockyard at Lothal, Gujarat, during the Harappan or Indus Valley Civilisation.

Harappan artifacts have been discovered at a number of coastal settlements around the Persian Gulf. Additionally, a number of Harappan artisanal production centers and habitation sites along the vast coastline, which stretches from the Makran coast in Pakistan near the Iranian border to Lothal in the Gulf of Khambhat, support the maritime trade activities of Lothal.

Approximately 222 meters long, 37 meters wide, and 4 meters deep, a sizable trapezoidal basin of baked bricks is found in Lothal's eastern region. The existence of an inlet and outlet channel, a 240-meter-wide mudbrick platform on the western edge to facilitate cargo handling, and the presence of a "warehouse" close to this structure are some of the features that lend credence to the dockyard theory.

This hypothesis, however, has been a subject of debate among scholars. Despite this evidence, some scholars, alternative theories have been proposed that consider the structure as a water reservoir for irrigation and human consumption.

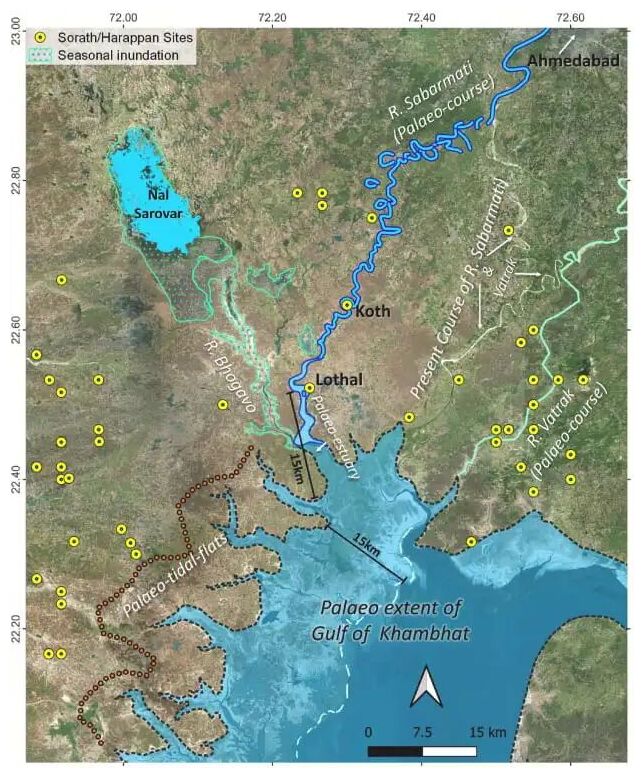

The study has revealed that the Sabarmati River used to flow by Lothal (currently, it flows 20 km away from the location) during the Harappan Civilisation. There was also a travel route connecting Ahmedabad, through Lothal, the Nal Sarovar wetland, and the Little Rann, to Dholavira — another Harappan site, according to analysis.

© E. Gupta et al.Reconstruction of the original course of the river through Lothal.

For their study, the researchers used data from early maps, satellite imagery, and digital elevation models — 3D models that represent the topography of a planet or celestial body.

The study was published in the Journal of Archaeological Science in August. It has been carried out by Ekta Gupta, V N Prabhakar, and Vikrant Jain of IITGn.

Speaking to The Indian Express, Prabhakar said, "Using the technology we could find a gradual shifting of the Sabarmati river where it reached its present-day course. One of these is coinciding with Lothal. So it means when Lothal was there as a Harappan port, definitely this river was flowing at the spot. The Nal Sarovar was in full flow out from which one river came out. So there was a connection from Lothal as one can directly go to the Nal Sarovar and from here to the Little Rann, then on to Dholavira. If one person travels by boat, he can reach there within two days. So this is how the traders might have traveled, transferred goods because, from Lothal, we have got the evidence of foreign trade."

The study suggests that traders came to Gujarat through the Gulf of Khambhat, probably went to Ratanpura to get materials, and carried them to Mesopotamia (modern-day Iraq).

Source: Ministry of Education of India

Reference: doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2024.106046

Source link