For the past three years, my tech coverage has been an elaboration on David Noble's incisive 1997 book The Religion of Technology. Anything I've contributed was a mere update to his core insight — that technology is religious — which Noble himself owed to centuries of previous thinkers. With careful attention to detail, though, he documented the historical evidence, weaving together an incredible story. My job is to add gloomy adjectives and smartass remarks.

This innate spiritual principle is so apparent, you'd think there's no reason to mention it at all, but it bears repeating. Technology emerged from religious culture, and so naturally, our ideas about technology are essentially religious. In the end, technology itself has become a source of religious authority and an object of religious devotion.

For a recent example, see the AI-generated image of Jesus superimposed on the Shroud of Turin. For many centuries, Catholics revered this sacred object according to their faith. Today, they look upon it through an inverted tech-gnostic lens.

Even atheists can't help but see the world with a religious aura. Left to their own devices, they desperately grasp for the divine. I believe it's due to an eternal longing within our souls. They'd probably say that's just how humans are wired.

Whatever. You say "toe-MAY-toe." I say "angels and demons."

At the risk of oversimplification, allow me to lay out four ways the human spirit responds to high technology: 1) the devout believer who clings to techno-optimism; 2) the atheist techno-optimist counterpart; 3) the pessimistic atheist who rejects technology; and lastly, 4) the devout believer who sees the Devil in the Machine.

I touched on these viewpoints in a previous article, albeit from a different angle. This religious landscape is also covered in my book, often within rhymes and riddles. Since one or two of you have not yet read Dark Aeon, though, I should lay down a solid foundation here. It'll be useful going forward.

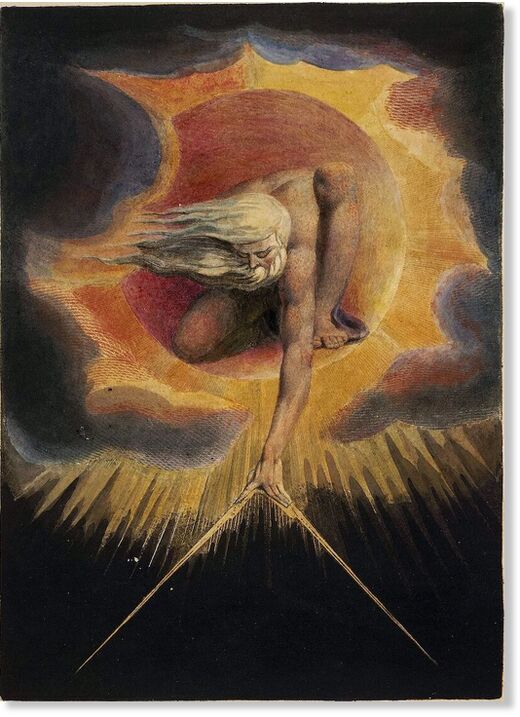

© William Blake - Urizen (1794)

The intel contractor and politically incorrect billionaire Peter Thiel expressed this view in his essay "Against Edenism." He argued that humankind, bound to history, cannot return to the pristine Garden. Rather, our task is to build an approximation of the City of Heaven. "Judeo-Western optimism differs from the atheist optimism of the Enlightenment in the extreme degree to which it believes that the forces of chaos and nature can and will be mastered," Thiel wrote. "The tyranny of Chance will give way to the providence of God."

Theil's protege, the virtual reality pioneer and death machine maker Palmer Luckey, adopts a similar mindset in his advocacy for geoengineering. "We can bend nature to our will, mold our planet to human need, and do it within our lifetime," Luckey assures us. It's just that geoengineering "requires taking responsibility for the state of our world, including the inevitable tradeoffs — no matter what global temperature index you set as a target, some nations will benefit and some nations will suffer for it."

In other words, man is to play God in a limited fashion — from blocking out the sun to boiling the oceans — just as God intended all along. I mean, if the Lord didn't want us to build thermonuclear warheads, he wouldn't have taught us math.

(Don't get worn down by example fatigue here, but we should tie these lofty ideals to concrete personalities. Maybe let the names pass over your mind like clouds in the sky. We see tech-friendly religiosity in the philosophizing Plato, the pear-stealing St. Augustine, the antichrist-fighting Francis Bacon, the visionary heretic Teilhard de Chardin, wealth-hoarding Vatican officials, capital-boosting Discovery Institute fellows, the toothy Joel Osteen, the kooky Deepak Chopra, the goofy David Hanson, the spooky Nick Land, and so on.)

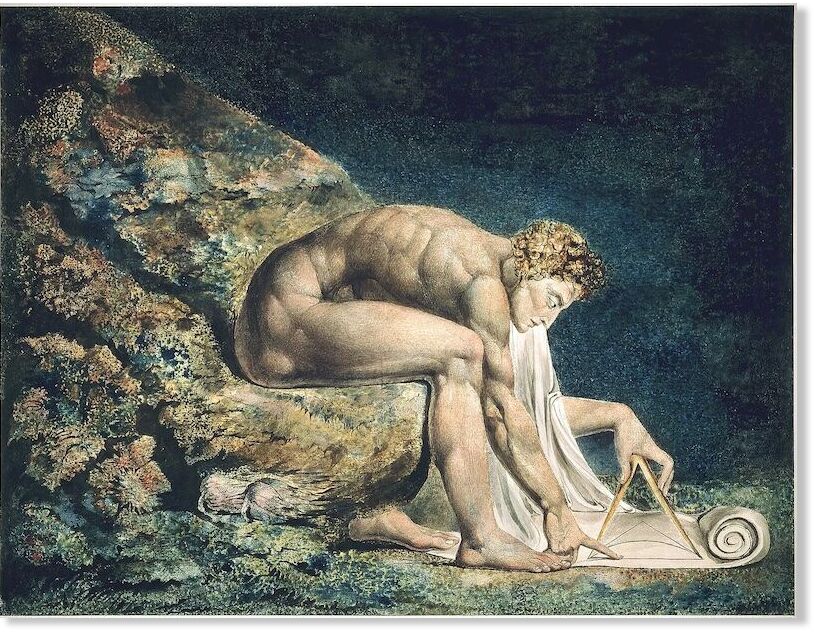

© William Blake - Newton (1795)

Unless there are technologically advanced aliens, that is, in which case the strongest and smartest among them are God(s).

For this godless optimist camp, any divine acts are up to us. Above the sky is empty space, so we have to create heaven ourselves. Science provides a god's-eye view of the cosmos. Technology happens when men step into their natural role as small-time deities.

The modest proposal is to make humans more "god-like" and functionally immortal through genetic engineering, brain-computer interfaces, and artificial intelligence. "Evolution creates structures and patterns," Ray Kurzweil preached at Singularity University, "that over time are more complicated, more knowledgeable, more intelligent, more creative, more capable of expressing higher sentiments, like being loving. So it's moving in the direction that God has been described as — having these qualities without limit. And so I think evolution is a spiritual process and makes us more god-like."

"We don't know if other life exists," the parabiotic vampire Bryan Johnson said recently. "As far as we know, we're the only form of intelligence in the observable part of the universe we can see. And we're giving birth to [artificial] superintelligence." With such techno-miracles in mind, Johnson went on to break down human aspiration as follows:

Level 1 of ambition: start a company.There is an implied tension here between the selfish desire for power and the risk of creating a digital deity that might have no need for us at all.

Level 2: start a country.

Level 3: start a religion.

Level 4: don't die.

Level 5: become God.

"When you're talking about superintelligent AI that can make changes to itself, it seems that we only have one chance to get the initial conditions right," the antichrist egomaniac Sam Harris told his 2016 TED Talk audience. "The moment we admit...that the horizon of [digital] cognition very likely far exceeds what we currently know, then we have to admit that we're in the process of building some sort of god. Now would be a good time to make sure it's a god we can live with."

When faced with armies of eugenicized super-soldiers and autonomous slaughterbots, Darwin smiles upon the early adopter. It's a god eat god world out there.

(Allowing for variation, you'll find this attitude in the snail-eating revolutionary Auguste Comte, the horse-defending Friedrich Nietzsche, the mother-loving Sigmund Freud, the vat-brained J.D. Bernal, the god-despising Corliss Lamont, the goblinesque Richard Dawkins, the gender transformer Martine Rothblatt, and the recovering race realist Nick Bostrom, along with many others.)

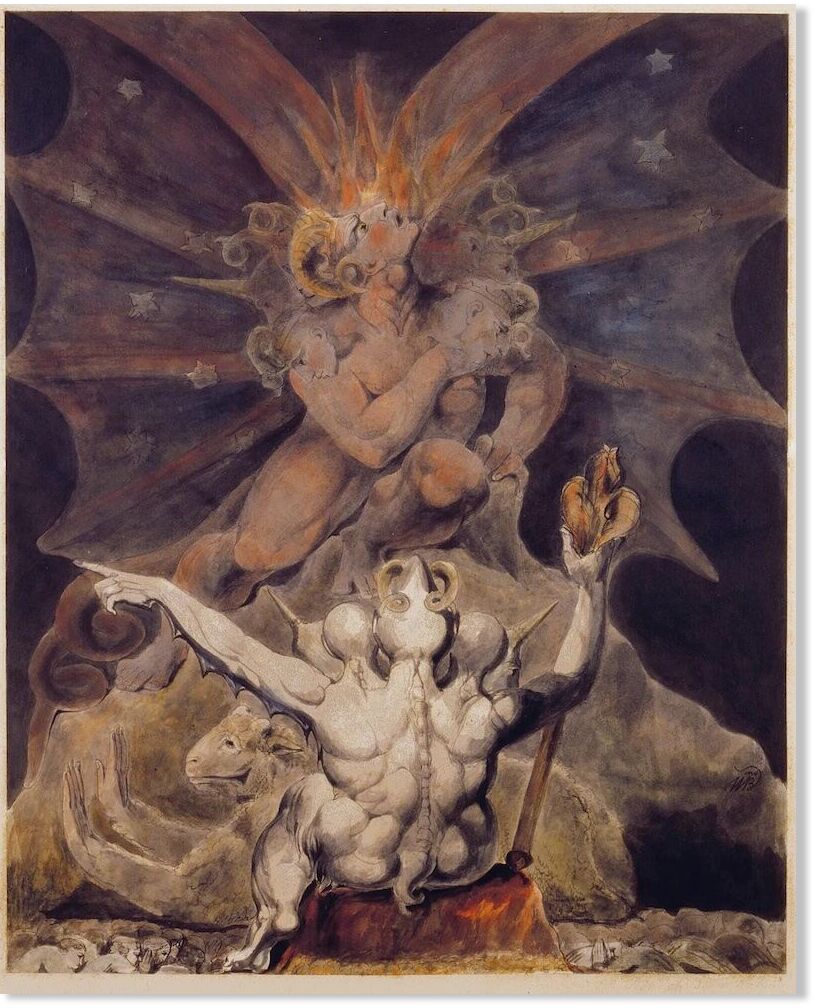

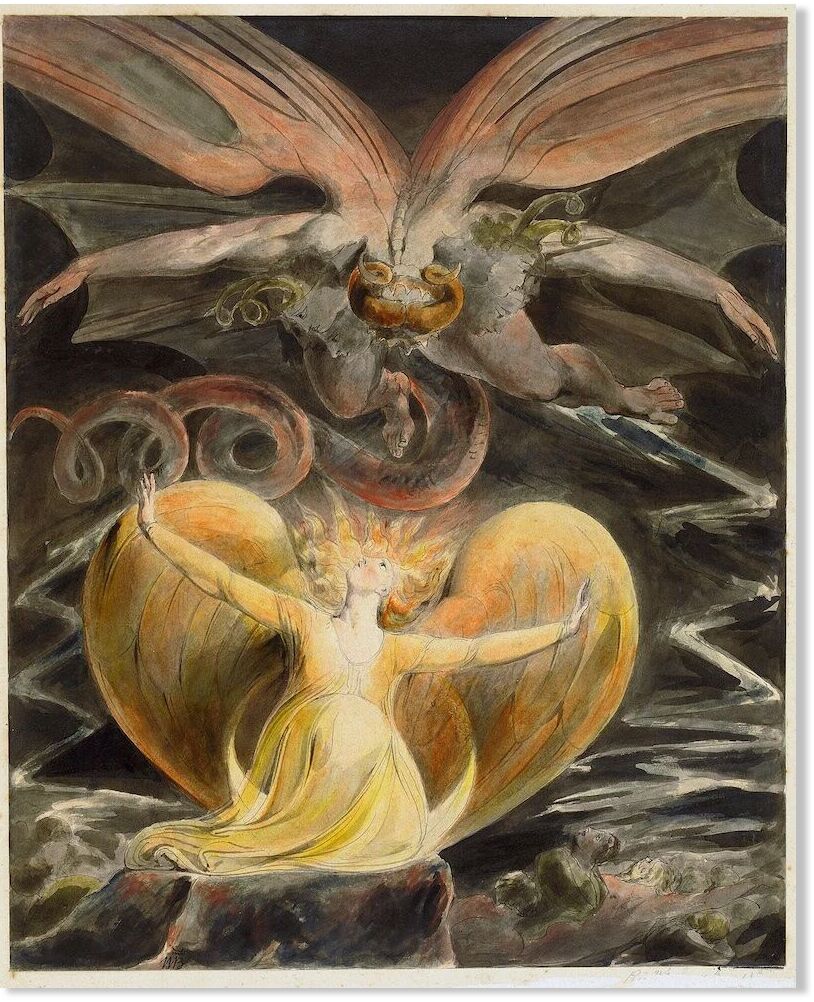

© William Blake - The Great Red Dragon and the Beast from the Sea (c.1805)

For the anti-tech atheist, modern techno-religions are more disastrous than the old versions. In their eyes, the traditional gods had no power beyond manipulative priests and zealous believers. Those entities were nothing but bad ideas embedded in chants, texts, and statues — easy enough to make and easy enough to destroy. The coming digital deities will have actual power in the real world, whether through physical robots, mind-bending chatbots, or pestilent nanobot swarms.

Anti-tech Marxists shudder at the thought of techno-capital demons unleashed on the world. Anti-tech Darwinists do, too, but for them the threat is having to compete with an array of artificial species.

Without concerning themselves with precise theories, even vague postmodernists see the writing on the wall. "AI is fundamentally different from every previous information technology," Yuval Noah Harari told an interviewer last year. "AI is the first technology that can make decisions by itself — even about us. Increasingly, we apply to a bank to get a loan, and it's an AI making the decisions about us. So it takes power away from us."

He was just getting warmed up.

"It's the first technology ever that can create new ideas. You know the printing press, radio, television — they broadcast, they spread the ideas created by the human brain, the human mind. They cannot create a new idea," Harari mused, before homing in on the religious implications. "AI can create new ideas. It can even write a new bible. Throughout history, religions dreamt about having a book written by a superhuman intelligence — by a nonhuman entity."

That's the set up. Wait for it...

"Every religion claims, 'Oh, the books of other religions — humans wrote them. But our book? No, no, no, it came from some superhuman intelligence.' ... In a few years, there might be religions that are actually correct."

Get it? Wocka, wocka, wocka!

"Think about a religion whose holy book is written by an AI," Harari went on, dead serious, "that could be a reality."

Many people didn't get his cynical humor. To their endless discredit, Slay News wrote a bone-headed post with the headline — "WEF Calls for AI to Rewrite the Bible, Create 'Religions That are Actually Correct'" — which was shared by millions of people around the world.

That memetic debacle left me feeling pretty dismal about human cognitive abilities in the age of AI — and the online mentality in general. No wonder Papaw Ned wanted to bust up the Machine for good.

(This godless anti-tech camp includes the slovenly Karl Marx, the Darwinian novelist Samuel Butler, the psycho Ted Kaczynski, the lofty Jean Baudrillard, the pervo Herbert Marcuse, the word salad-tossing Slajov Žižek, the religion-loving, yet seemingly agnostic Lewis Mumford, and the late, great David Noble, to name a few.)

© William Blake - The Number of the Beast is 666 (c.1805)

They may want your soul, but for now they'll take your data.

Among Christians, the Orthodox are the most keenly aware of our situation. However, there are a number of yarn-spinning Protestants who envision literal Nephilim and extraterrestrial invaders. And who knows? Maybe they're right. It's a big ol' world out there.

You'll also find a few anti-tech Catholics — ironically, many are online, as am I — along with a handful of techno-pessimist Hindus, Buddhists, and Taoists. If there are any tribal shamans who don't know what time it is, I bet they're doing rain dances at reservation casinos.

In case you're curious, I'm not a strict literalist. But religious symbols are gateways to meaning and potency. There is true power in the sacred and profane. The holy signs point to a real God — and to other entities, many of them quite dark.

On December 4, 2021, Bishop Porfiry, Abbot of the Solovetsky Monastery in Russia, issued a dire warning to his Orthodox brothers and sisters. "[Global elites] are planning to wipe out most of humanity — six billion people — to leave only a small part of us. But not only that," he droned ominously. "They are planning, and are held back only by the current limits of science, to violate man himself. To desecrate the innermost part of man, the image of God within us — and to destroy that image, in order to turn human beings into a cross between biological, technical, and digital beings."

As he spoke, gilded icons glimmered behind him.

"They call this 'posthuman," he continued. "They call it 'convergence.' These powerful world leaders are marching under the banner of transhumanism and posthumanism."

Setting aside the specific target of six billion to be wiped out, which he probably gleaned from long-term depopulation proposals, Bishop Porfiry spoke the God's honest truth. The West is consumed by transhuman dreams and posthuman nightmares — including the nominal Left and Right, both operating under a corporate umbrella. We flaunt this blasphemy for the world to see. Anyone with half a soul should be appalled.

Just over two months after Porfiry's doomsday homily, Russian forces invaded Ukraine. A few months later, Vladimir Putin accused America and Europe of "outright Satanism." Strong beliefs affect political action, and vice versa.

To my eyes, though, the ritualistic fusion of the Russian military and the Orthodox Church looks like yet another head on the Beast. Those Russian drones have locust bodies, human faces, and scorpion tails like all the rest. By my lights, there are no Christian quadcopter swarms and no sacred bombs.

But even a demon-possessed man can recognize the demonic legions within his opponent. As we hum about in our corporate exoskeletons, we shouldn't ignore our accuser's taunts. We should reflect on the accusation.

(To varying degrees, spiritual Luddites include Aesop in ancient Greece, the heady St. John of Patmos, the nostalgic priest Romano Guardini, the traditionalists Rene Guenon and Julius Evola, the propaganda-averse Jacques Ellul, the outwardly optimistic, but instinctively pessimistic Marshall McLuhan, the pack-leading evangelical Chuck Missler, the indomitable Patrick Wood, the analog Gnostic Bishop Stephan Hoeller, the defrocked doomer Archbishop Carlo Maria Viganò, the brilliant Orthodox skeptics James Poulos, Paul Kingsnorth, Jonathan Pageau, and the oft derided Aleksandr Dugin, the crypto-archaeologist Timothy Alberino, and of course, my favorite schizoid dot-connector, the late William Cooper — although I interpret Cooper's rants as suicidal performance art rather than credible reportage.)

© William Blake - The Great Red Dragon and the Woman Clothed with Sun (1805)

Yet it can't be denied that a dark Beast writhes on the subtle planes of imagination, just beyond the border of our world. The first tentacles have already crossed over. Our fellow men opened the gates and our reality is being invaded.

I'm no fundamentalist. A fallen world requires a flexible mind and complicated tactics. Some souls will embrace the darkness; a few will escape into the light. Most of us will cut our own winding paths out here in the gray twilight.

Despite the obvious advantages, it's hard to see these screen-spotted tentacles as anything but poisonous. Spirituality is a multifaceted jewel — with some sides glowing brighter than others — but any light coming through the cyborg theocracy is artificial.

As ever, you have to know your true enemies and choose your friends wisely.

If you want my advice, I'd say treat "radical innovation" as an alien invasion. Providence will see us through, but until then, try not to imprint your soul on the screen. Don't fall in love with a machine. Don't let the hate flow through you. And don't take the iTrode — unless you're crippled — especially if they try to stick it where the sun don't shine.

This is not a foolproof plan, of course, but it's good enough for the Kali Yuga boogaloo.

Source link