'A Quiet Place: Day One' saves the cat, spares the monsters

I have fond memories of taking two of my children to see "A Quiet Place Part II" in Topsham, Maine, in the summer of 2020. My son pronounced it the "scariest movie he'd ever seen" and reported trying to make as little noise as possible during a bathroom visit right after the credits rolled.

His high estimation of the film may have had to do with his age: he was 6 at the time. In retrospect, a little young, but I can't say I feel very guilty about it. The three "A Quiet Place" installments are resolutely PG-13, the kind of more or less wholesome cinematic roller-coaster ride Steven Spielberg used to excel at.

In our current age of managed decline, watching terrified, demoralized Americans abandon one of our greatest cities isn't much fun.

At that point in his life, my son couldn't have had more than 30 movies to which to compare "A Quiet Place Part II." He hadn't even seen the first one. My then 10-year-old daughter had, and her review of the sequel was a little more mixed. She'd enjoyed it while watching it, but as the thrill of the jump scares faded during the car ride home, she mentioned her disappointment that it really didn't do anything new.

Blunt force

I had to agree. 2018's "A Quiet Place" ended on a note of defiance. Having discovered the enemy's weakness — and a clever method of targeting it — Emily Blunt's Evelyn Abbott seemed poised to become an unsmiling killing machine a la Linda Hamilton in "Terminator 2." Perhaps director/star John Krasinski would follow the example of the "Alien" series and make the first sequel more of an action movie.

Alas, apart from an entertaining prologue — an effective flashback to the day the creatures landed in the Abbott's small town — "A Quiet Place Part II" pretty much stuck to formula, keeping our heroes on the defensive and exploring more scenarios in which characters simply must not make a sound, despite being very, very tempted to do so.

The first movie gave us what is arguably the ultimate such scenario — giving birth (while also having just stepped on a nail). Its follow-up finds nothing so memorable. We do meet other survivors — but mainly for the usual "the biggest monster of all is man" routine that has been more effectively explored in "The Walking Dead," to name one example. It's hardly an improvement on the original's claustrophobic dread. And once again the movie reminds us that we know how to kill these things. But we still don't, at least not at any meaningful scale.

Perhaps this will be addressed by the upcoming "A Quiet Place Part III." In the meantime we have the official prequel, "A Quiet Place: Day One," which my children and I saw at the same movie theater where we enjoyed its predecessor four years ago.

Slice of life

Like fellow horror icons Jason Voorhees and Ghostface, the Death Angels have hit the big time: New York City. Bigger may not be better, but it is louder: An opening intertitle mentions that NYC generally maintains an ambient volume of 90 decibels, about the same level as a human scream.

This factoid is meant to be ominous, but my first thought was: Wouldn't all that noise make it easier to hide? Much of what made "A Quiet Place" so suspenseful was the utter stillness of the countryside, in which the snap of a branch echoed like an explosion. The city does quiet down quite a bit as it empties out, but characters holed up in a Manhattan storefront or apartment simply don't feel as terrifyingly isolated as the Abbotts did in their farmhouse.

Our hero this time is Sam (Lupita Nyong'o), a dying poet living in hospice outside the city. Like many terminally ill movie characters, Sam has a bad attitude about her imminent death; in fact, she's only able to muster affection for her service cat, Frodo. The promise of one last slice of real New York pizza is enough to convince Sam to join her hospice mates on a field trip to Manhattan; we share her horror when it's revealed that this particular outing is to a marionette theater.

Sam's despair deepens as the invasion begins. Whatever's happening, it's serious enough that they'll have to head back to the hospice without getting pizza. Once the monsters show up in earnest, its clear that nobody's going anywhere, at least not by bus.

Nyong'o is a good actress, and she makes us understand how important getting this pizza has become to Sam. There's nothing mannered or cutesy about it; she displays real anguish and barely contained fury when it's denied her. So it's not hard to buy in to Sam's mission. While everyone else is heading downtown to be evacuated via the South Street Seaport, Sam (still with Frodo) is headed to Harlem to the legendary Patsy's Pizzeria.

A real drip

Along the way she runs into Eric (Joseph Quinn), a young and terrified British law student. We first see Eric emerge gasping for air from a flooded subway tunnel. His suit is drenched, of course, and he also turns out to be "wet" in the British sense of the word: weak, ineffectual, without personality. He begs Sam to let him come with her; eventually she relents.

Is this supposed to be one of those "woke" role reversals I keep hearing about? This time we'll have the guy play the helpless girl? But that doesn't make sense; it's not as if anyone likes that kind of character when played by a woman. These otherwise functional, able-bodied adults exist as annoying plot contrivances, dead weight there just to make the protagonist's life harder.

Whoever marketed this movie must have had reservations about how this role reversal would play; on the movie's ugly, photoshopped-looking poster (increasingly common these days), it is Nyong'o who stifles a scream, while Quinn exudes bland determination.

Eric does nearly get them both killed at least once; he also lets her lead the way, while he cringes behind her likes she's a human shield. This is all the more jarring as Nyong'o is not what you'd call a "Mary Sue." She's also very scared; her silent emoting is one of selling points of the movie. So what does she see in this guy?

Eric's uselessness becomes a real problem when we get to his character's real function: He's there to help Sam "learn how to live." He does this with a classic "nice guy" move. While a more survival-oriented alpha would have been too busy planning their escape, Eric takes the time to really listen to Sam's boilerplate backstory; when the time is right, he knows just what to do to cheer her up.

Perhaps I'm being too hard on "A Quiet Place: Day One." My kids enjoyed it. And I did too, to some extent; I've never not been "gotten" by a jump scare, and this movie has some decent ones. But I daresay the filmmakers are overestimating our interest in an "origin story" for these interstellar man-eaters. "A Quiet Place" is fun because it plunges us into the action in media res. Our minds trying to fill in the gaps adds to the terror.

No church in the wild

Variety recently called the "Quiet Place" trilogy "one of horror's most reliable box-office franchises." I for one am sincerely glad for its consistency. It hits that sweet spot for the parent of pre-teens and teens: chills without gore or sex that the whole family can enjoy. I won't complain if they keep cranking them out at this level of quality.

But I doubt I'll bother going on my own. It turns out these monsters just aren't that interesting beyond their central gimmick. The characters in "A Quiet Place: Day One" may be experiencing all this for the first time, but it's our third go-round. After a while, all the shushing makes you feel like you're in a library.

The screenwriting rule that you should endear your character to the audience by having him or her "save the cat" is a cliche by now; I'm not the first one to point out that Sam has a literal "save the cat" moment here.

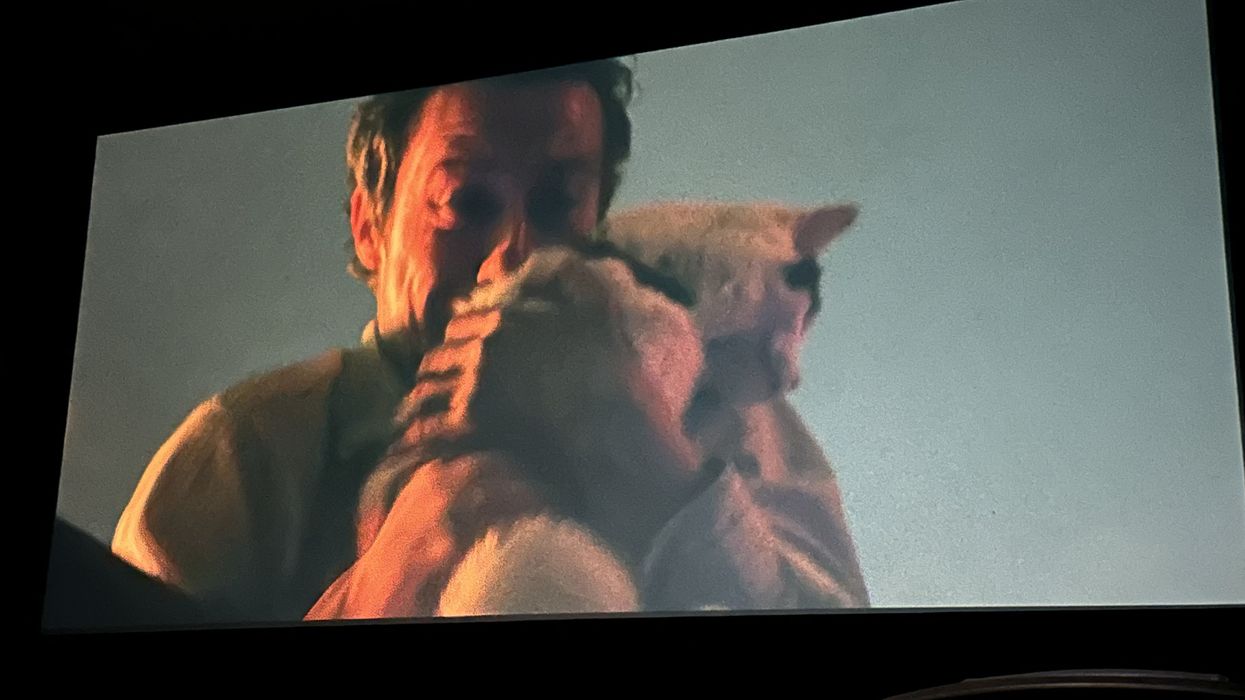

The problem is that Frodo (well played by two different cats, Schnitzel and Nico) emerges as the most likeable character by far. Even the little Sam and Quinn do say is too much; the completely silent feline is beautiful to watch in a way that the human characters, saddled by the script's hokey therapeutic concerns, just aren't.

At one point Sam and Eric find themselves huddled with other survivors in a beautiful, bombed-out church. But it's just a pleasant way station on their pilgrimage to Sam's own personal holy site: the jazz club where she used to watch her father play piano. Who needs prayers when you can get "closure"?

But what if they did pray? God might give them the courage to persevere — and with it, the obligation to embrace suffering and maybe even to keep fighting. When self-care is your religion, you face no such demands. Resignation and helplessness become virtues, as does comfort. The most noble end we can all hope for is to die "on our own terms."

That's how you end up with assisted suicide. During peak COVID, there was something a little too close to home in the spectacle of Americans huddled together indoors, too scared to make a peep. And in our current age of managed decline, watching terrified, demoralized Americans abandon one of our greatest cities isn't much fun either.

To paraphrase a certain presidential candidate, I like horror movie heroes who don't get killed. Deep down, most of us do. America needs a win; I hereby call for a moratorium on miserabilist blockbusters until morale improves. Haven't we had enough pussyfooting around?

Source link