I'm thankful for the reality of good and evil

Christ is King.

Satan is real.

In a strange way, I'm thankful for both. It's not that I'm happy about the principalities and powers with which we do battle in this fallen world, of course. But I thank God for the wisdom to seem them for what they are.

'Wisdom is the recovery of innocence at the far end of experience.'

Satan is real.

It's a sentence I would have been embarrassed to speak just a few years ago. Perhaps you're familiar with that famous bell curve meme? At one end you have the simpleton, at the other the genius. The joke is that both extremes believe the simple, unadorned truth: In this case, Satan is real.

In the middle we find the educated modern — or midwit. Not for him a crude, three-word fact. Sentences and sentences of hemming and hawing, qualifications and hedges, intellectural frippery. That's where I was for most of my life. That's the sweet spot for the American elite and those who aspire to it.

That worldview worked, until it didn't. The first step to acquiring wisdom was realizing I wasn't nearly as smart as I thought I was.

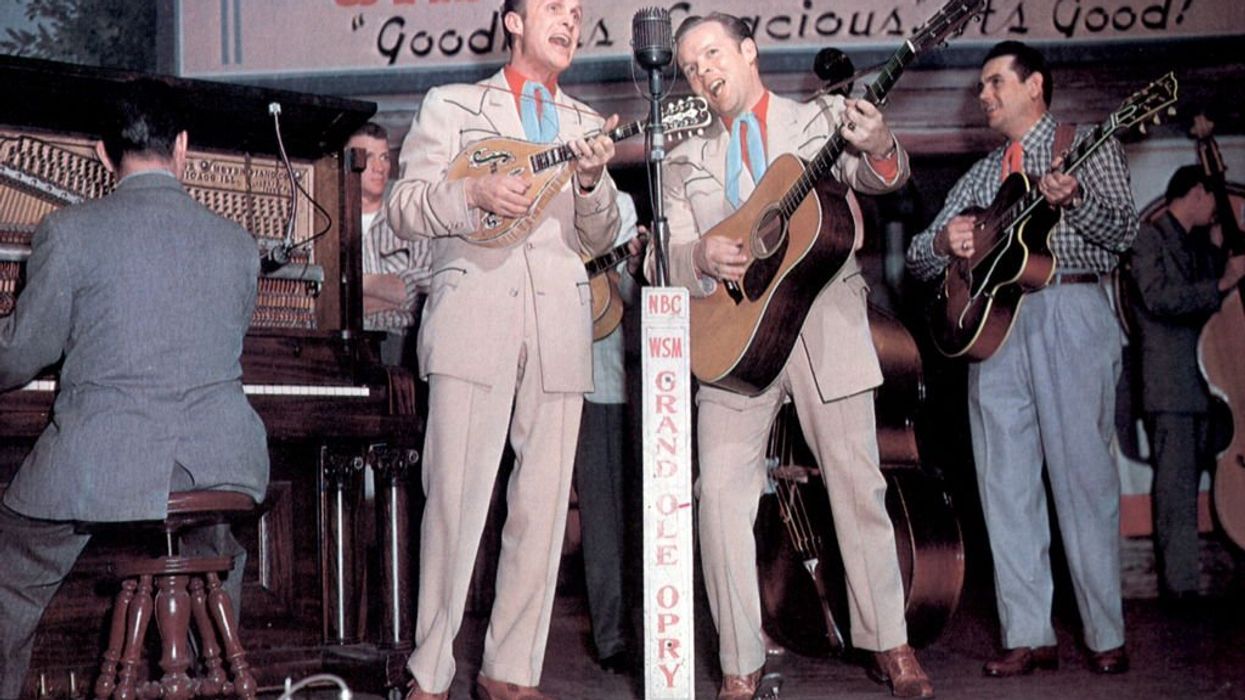

The cover of the the Louvin Brothers' 1959 country gospel album "Satan is Real" regularly shows up on those clickbait lists of weird album covers. It's the kind of goofy kitsch I used to love with an affectionate sense of superiority.

It strikes me a little different now.

The brothers didn't hire a professional to design the cover of "Satan is Real," and it shows. The image — featuring a 12-foot plywood devil Ira Louvin built himself, backlit by burning, kerosene-soaked tires — has been widely shared for its kitsch appeal. And yet the eerie power and urgency of songs like the title track or “The Drunkard's Doom” can make you wonder if maybe they're right.

The Louvin Brothers' homemade hell can't compete with the far more immersive depictions of the demonic offered on today's screens. And yet few of these visions spring from genuine conviction.

We don't take evil seriously, especially not supernatural evil. But we're like the obnoxious preteen who's only recently outgrown Halloween, walking through the haunted house and gleefully pointing out how “fake” everything is. Just who is he trying to convince?

I remember how easy it was for me to dismiss the notion of supernatural evil.

The occult isn’t what it used to be. We’d need the firewood from a thousand Burning Mans to dispatch every witch casting spells on TikTok, but their “magick” tends to focus on self-realization and wellness, like yoga for people with purple hair and face piercings.

Child sacrifice in the form of abortion persists, but many of its practitioners are only dimly aware of the death cult they serve. Even the pants-soilingly grueling ayahuasca trips now in vogue don’t seem to pose any eternal risk; all spirits encountered are assumed to have our best interests at heart.

Current popular entertainment tends to reflect this shallow and naïve understanding of the unseen world. Rare is the artist who dares remind us of what might really be stake in these lives we lead.

This is why the sickening dread evoked by Irish director Liam Gavin's 2016 movie "A Dark Song" is so unfamiliar.

Two people meet in a remote farmhouse in rural Wales: a desperate, grieving mother, and the bitter, alcoholic occultist she’s hired to help her contact her recently murdered young son. They begin an arduous, months-long ritual, which writer-director Liam Gavin depicts with painstaking realism.

By showing how tedious and grubby the path to damnation can be, "A Dark Song" makes us ponder our own demons and the disturbing possibility that we’re not as in control of them as we’d like to think. Someday we may reach out to remove the mask, only to find that our deepest childhood instincts about what lurks in the dark were right all along.

“Wisdom is the recovery of innocence at the far end of experience,” says Orthodox theologian David Bentley Hart. I'm grateful every day for a new chance at cultivating this wisdom — and I wish the same for you.

Happy Thanksgiving.

Source link