By Benjamin Picton, Senior Macro Strategist at Rabobank

Meditations In An Emergency

It’s now less than a week to go until the USA decides who is going to be their next President. The state of the political discourse recalls the ‘dramatic crossroads’ meme, where the respective labels attached to the sunny uplands and the grim castle of doom is a Rorschach test to confirm our political priors.

I’ve chosen my words deliberately to say that the USA will be deciding on their next President - rather than the next ‘leader of the free world’ - because one of the options on the table is a more isolationist approach to trade and foreign policy where the USA may decline to perform the leadership role, instead prodding oftentimes recalcitrant allies into shouldering more of the global security burden.

That could draw the curtain on the ‘Team America World Police’ neocon phase, or even Woodrow Wilson’s “making the world safe for democracy” idyll, if you prefer to cast your view further back. What’s now clear is that the bond market and the DXY is becoming sensitized to the potential implications of another Trump win.

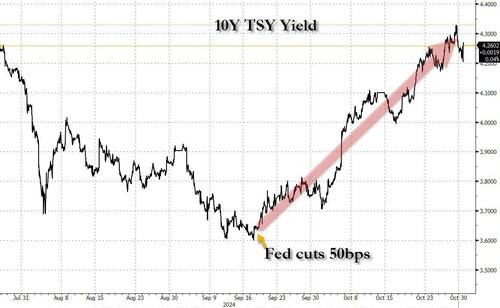

US 10-year yields were down almost 3bps overnight, but are up more than 55bps since the Fed cut rate in mid-September. Americans who had been holding out for rate cuts before they went house shopping are again contending with mortgage rates beginning with a 7-handle, because US mortgages tend to be priced off the long end of the yield curve.

The shape of the curve is telling. While the OIS futures strip has pared back prospects for further rate cuts from the Fed this year, the 2s10s Treasury spread has continued to steepen. The 2s10s was still inverted at the beginning of September, but now records a positive slope of 15.5bps even as the whole curve has shifted higher. Curiously, the 2s30s spread has not steepened at all since the Fed cut rates.

What does this tell us? In a nutshell, markets are banking on fewer rate cuts in the near term and a decade ahead where inflation may be higher than we have grown accustomed to in the recent past. Why might that be? As Donald Trump’s odds of winning the election improve, markets are re-pricing assets to reflect a state of the world in which the Trump policy suite is implemented. Trump himself is a big spender who favors sweeping tax cuts and universal tariffs that most economists will tell you are inflationary, but a Trump win isn’t the only bear case for bonds.

Harris herself is no fiscal hawk, and there is also a renewed uneasiness over the global debt burden and the likelihood of that debt burden growing further as nations confront higher spending on health, aged care, national defense and interest expenses. More on that later.

The recent price action looks like a win for Rational Expectations Theory, but some other elements of economic theory are also having their time in the sun. The concept of low but stable inflation targets being a good thing is borne of the idea of ‘nominal rigidities’. Essentially, this is the contention that certain prices in the economy are ‘sticky’, and that markets are therefore not self-equilibrating in the way that classical economists might ordinarily suggest.

An example of this might be the decline in the volume of US home sales as vendors refuse to adjust price expectations to reflect prevailing economic conditions. Another example might be the proposed 10% cut to the wages of Volkswagen autoworkers (sure to be opposed by labour unions) in Germany that comes courtesy of Europe losing the competition race to China.

In both instances, market offers (for houses and labor) have remained sticky and not adjusted to cold economic reality. The bid/offer spread has widened out, and transaction activity dries up. How do New Keynesian economists of the type that dominate central banking and national treasuries solve such a problem? They grease the wheels of the economic machine by creating enough inflation for bid prices to rise to meet those sticky offers.

We might get some hints of this kind of thinking later today when UK Chancellor Rachel Reeves delivers her first budget. In a document likely to be light on surprises, Chancellor Reeves is set to redefine how the UK measures debt so that it can borrow more to “invest”. The UK already exceeds the 90% debt-to-GDP threshold that Carmen Reinhart and Ken Rogoff famously (or infamously) estimated to be the point at which the Keynesian multiplier falls below one. In layman’s terms, this means that for every extra dollar that the government spends GDP increases by less than one dollar, thereby rendering borrow and spend stimulus measures self-defeating as debt grows faster than GDP.

How to escape this economic doom loop? The options are default or retrenchment (austerity). We can rule out austerity as something that no government is brave (or foolhardy) enough to seriously propose after previous attempts by George Osborne and Wolfgang Schauble severely frayed the social contract. On the default side of the menu, countries that have no power over the issuance of their own currency are constrained to hard default (think Greece), whereas sovereign currency-issuing governments have the luxury of defaulting sneakily by debasing the coinage of the realm.

This is the financial repression scenario where bondholders are the patsies, financing fiscal profligacy by holding securities that yield negative real returns. Under this scenario, the smart money gets out of bonds and holds real assets that provide an inflation hedge. With the S&P500 up more than 22% YTD and long yields rising, is this the future that markets are now envisaging in what is beginning to look like a debt emergency?

Source link