All Global Research articles can be read in 51 languages by activating the Translate Website button below the author’s name (only available in desktop version).

To receive Global Research’s Daily Newsletter (selected articles), click here.

Click the share button above to email/forward this article to your friends and colleagues. Follow us on Instagram and Twitter and subscribe to our Telegram Channel. Feel free to repost and share widely Global Research articles.

Spread the Truth, Refer a Friend to Global Research

***

Abstract

Despite being a party to the Refugee Convention since 1981, Japan has historically admitted very few asylum seekers. However, recently the country’s total protection rate has increased, from 2.3% in 2020 to 52% in 2022. This article explores this seemingly dramatic shift in Japan’s refugee policy, tying the increased rate of asylum admissions to the country’s broader foreign policy in the face of recent geopolitical challenges in Myanmar, Afghanistan, and Ukraine, while outlining the diverging pathways of admission utilized in each case.

*

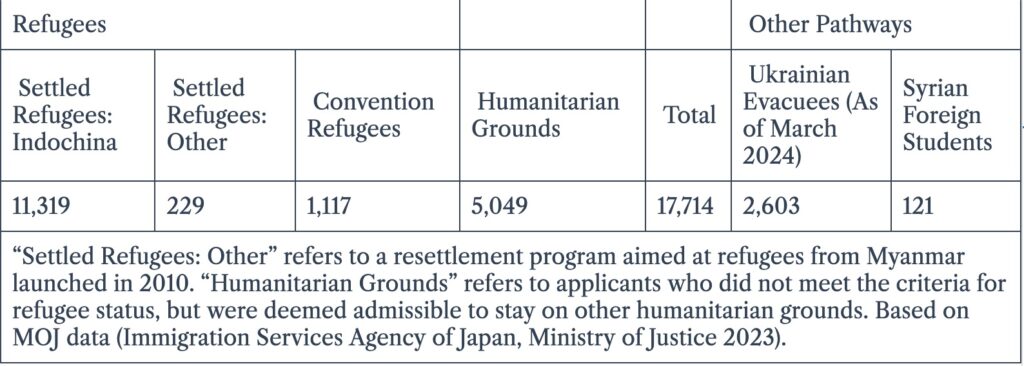

Japan’s modern refugee policy began in earnest following the fall of Saigon in 1975, which marked the end of the Vietnam War and resulted in the Indochina refugee crisis. During the later stages of the war and its aftermath, Japan had to balance its relationship with the U.S. and its strategic interest for stability in the region, gradually moving towards engagement with North Vietnam and a push for peace (Pressello 2023). While the country began to invest massively in the region, both through reparations for its role in World War 2 and Official Development Assistance (ODA), Japan initially did not take on a pro-active role in dealing with the refugee crisis (Havens 1990). As the number of refugees fleeing the region increased towards its peak in the years 1978–80, so did both domestic and international pressure on the Japanese government. Eventually, the country reversed course from being a transit country for Indochinese refugees to hosting them. Successive cabinet decisions, starting with the one on April 28, 1978, gradually expanded the admission quota and support for their resettlement (Ministry of Justice 2012). In all, Japan would admit 11,319 Indochinese refugees (see Table 1)—a small number given the scope of the crisis, but significant for the country’s refugee policy trajectory. Indeed, this experience would directly lead to Japan acceding to the Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees in 1981, and then to the Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees in 1982.

Japan as a “Negative Case” of Refugee Admission

Since then, Japan’s refugee policy has arguably built on the historical antecedent of its immediate post-Vietnam War approach of primarily extending financial assistance—a form of “checkbook diplomacy.” The country has contributed significant financial aid towards the protection and resettlement of refugees, most notably by being one of the largest individual donor countries to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR): Japan gave more than US$167 million in 2022. At the same time, it has admitted an extremely small number of asylum seekers to the country. In the four-plus decades since ratifying the Convention and Protocol, Japan has only admitted a total of 6,395 asylum seekers—although, this figure does not count the 2,603 Ukrainian evacuees it has admitted since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the 121 Syrian foreign students admitted under a special program launched in 2016, which was developed in coordination with the UNHCR with the goal of creating educational opportunities for young Syrians fleeing the civil war. Still, this is a lower total number than what many of Japan’s close allies in North America and Europe admit in a single year. For example, Germany granted humanitarian protection to 137,101 applicants in 2023, while the United Kingdom did so for 62,336 asylum seekers (Federal Office for Migration and Refugees 2024; Home Office 2024).

One reason for Japan’s low admittance of refugees is its geographical location as an island nation in East Asia, far removed from the major modern refugee-producing areas in the Middle East and Africa. However, geography alone cannot explain Japan’s reluctance to extend refuge to those needing protection—the country could, for instance, follow the Canadian model of resettling a set number of refugees that have been granted protection elsewhere.

Table 1: Total Number of Asylum Seekers Admitted to Japan, 1978–2022

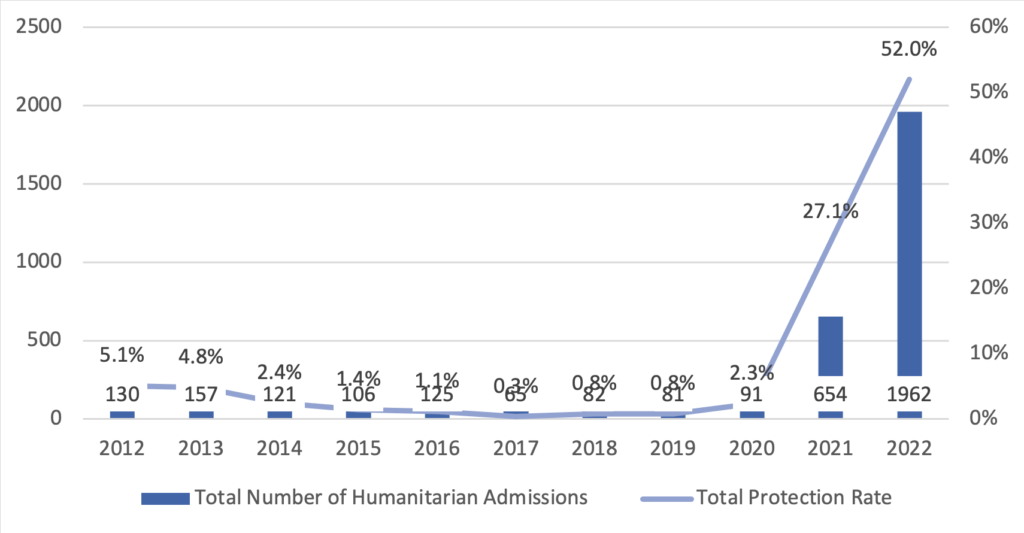

There is another reason for the low amount of asylum seekers granted protection in Japan: the country’s miniscule rate of recognizing asylum. In the year with the largest number of asylum seekers on record, 2017, Japan granted protection to 65 applicants out of a total of 19,629, for a total protection rate (TPR) of 0.33% (Immigration Services Agency of Japan, Ministry of Justice 2023b). The TPR combines the rate of refugee recognitions with the rate of asylum seekers admitted on general humanitarian grounds and is the UNHCR’s preferred measure to gauge the rate at which countries offer protection. More recently, in 2020, Japan’s rate stood at 2.3%. Overall, both the historically low absolute numbers of asylum seekers granted protection, and the rate at which protection is granted, stand in clear contrast to Japan’s generous financial contributions to the UNHCR.

It follows then that it is Japan’s particular aversion to accepting asylum seekers that has led to broad-ranging scholarship attempting to explain why this is the case. These include studies that focus on a broader transnational perspective. While Japan’s admission of Indochinese refugees has been attributed, at least in part, to international pressure (Havens 1990; Strausz 2012), this pressure has since not existed as a coercion mechanism (Wolman 2015). Other scholars focus on domestic dynamics, including Japan’s national identity as a homogenous country (Tarumoto 2019), domestic politics more generally (Kalicki 2019), and more technical institutional factors. For instance, scholars have pointed out the strict application of refugee law and high burden of proof as evidence of bureaucratic “rigidity” in the Ministry of Justice (MOJ), the primary governmental organ responsible for the administration of refugee policy (Akashi 2006). Even very recently published articles cited Japan’s low refugee recognition rate as one reason why Japan is failing to live up to its commitments to the rules-based international system it rhetorically champions (Hein 2023). In migration studies, scholars often talk about “positive” and “negative” cases of migrant labor admission, with the historic example of post-war Japan until the 1980s famously being cited as a negative case (Bartram 2000). Both Japan’s record on refugee protection and previous scholarship makes it clear that the country has been, for almost the entirety of its post-war history, a negative case of refugee admission.

Recent Trends: Granting Asylum at Historic Rates

In the last two years, however, both the total number of asylum seekers that have been granted protection as well as Japan’s TPR have increased significantly (see Figure 1). The TPR increased to 27.1% in 2021 and reached 52% in 2022. In that year, Japan granted protection to 1,962 out of 3,772 asylum seekers. Again, these figures do not include the more than 2,500 Ukrainians Japan has admitted since February 2022. Considering these developments, this article reconsiders Japan as a negative case of refugee admission and outlines how and why Japan’s refugee policy has seemingly undergone this rapid shift. While considering recent changes on the institutional level and other domestic factors, I will focus primarily on the changing origin countries of those asylum seekers admitted and their geopolitical context.

Figure 1: Japan’s Total Number of Humanitarian Admissions and TPR, 2012–2022

Figure created by the author based on MOJ data (Immigration Services Agency of Japan, Ministry of Justice 2023b).

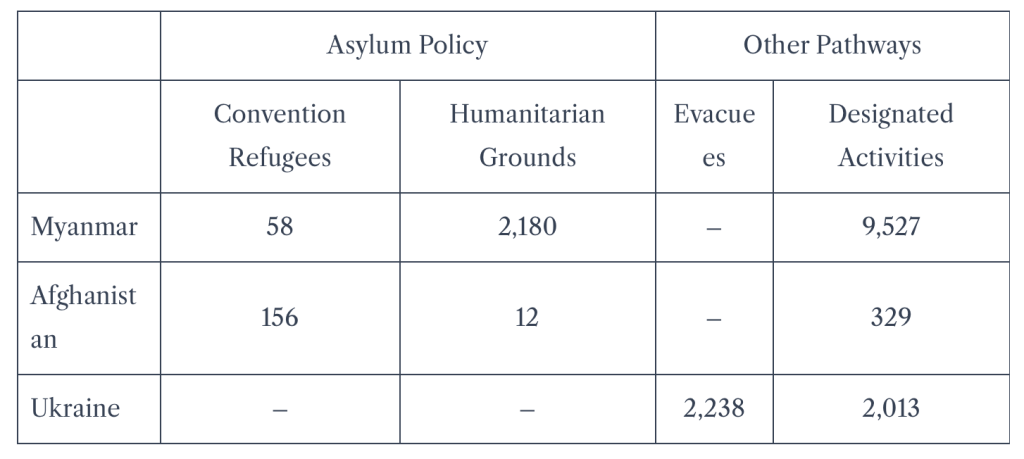

There are three countries that have accounted for the majority of recent humanitarian admissions to Japan: Myanmar, Afghanistan, and Ukraine. However, policymakers have utilized a very different approach for each, sometimes relying on already established legal pathways, sometimes adopting a new legal framework, and sometimes implementing a combination of both. The second major aspect of this analysis will thus be to outline the background as to why Japan has adopted these diverging pathways, which relate closely to the specific circumstances surrounding each country.

Therefore, I will develop my analysis by discussing the Japanese approach to humanitarian admissions from these countries as three separate case studies. To go into more detail, these are: (1) the liberal granting of right of stay on humanitarian grounds for citizens of Myanmar following the January 2021 coup d’état; (2) the blanket recognition of charter refugee status for a subset of Afghani citizens following the Taliban takeover in August 2021; (3) the admission of Ukrainian evacuees following Russia’s invasion in 2022. Beyond refugee policy, these three events—in combination with a broader geopolitical shift in the region—have led to Japan adapting its foreign policy. I argue that Japan’s recent shift to grant more asylum seekers protection can be understood as part of these foreign policy changes, which includes more pro-active regional and international engagement, as well as a recommitment to international and transnational institutions framed within values-based language. In my conclusion, I question whether Japan’s recent policy shift is sustainable, considering both the geopolitical factors that made it possible as well as recent concrete policy changes. This paper is sourced mainly on primary government documents—including from the political executive (e.g., the Cabinet Secretariat), the MOJ, and National Diet recordings—and augmented by secondary academic sources to provide additional context as necessary.

The Changing Origin Countries of Asylum Seekers and Grantees

Before looking at the three case studies in detail, it is important to compare the origin countries of both applicants and those admitted for asylum in 2017 and 2022 to establish change over time. 2017 was the year with both the highest number of asylum seekers and lowest TPR on record. 2022 is the latest year for which data is available at time of writing and thus the most relevant for an up-to-date comparison. As outlined above, both the total number of asylum seekers granted protection (65 in 2017, 1962 in 2022) and the TPR (0.33% 2017, 52% in 2022) have increased significantly in what is a relatively short time. Table 2 shows the top five origin countries for both asylum seekers and those granted protection for the two years in question.

Table 2: Top Five Origin Countries, Asylum Seekers and Grantees, 2017/2022

“Granted Protection” refers to both formal refugee status and recognition of stay based on humanitarian grounds. Based on MOJ data (Immigration Services Agency of Japan, Ministry of Justice 2018; 2023a).

While the reduction in overall applicants can probably be explained due to the lingering effects of border control measures following the COVID-19 pandemic, a quick glance at Table 2 shows two other significant trends. First, there is a discrepancy in the origin countries of applicants and those granted protection—persons being granted asylum in Japan generally do not come from the same countries that account for most applicants. This is especially evident in the data for 2017 and relates to the primary reason that the Japanese government has historically given to explain its low acceptance rate: that most applicants do not come from major refugee producing countries and are rather economic migrants seeking a pathway to residence in Japan. Indeed, the MOJ gave the following reasoning for its low TPR in 2017:

“Based on the UNHCR’s press release titled “Global Trends 2016” (released June 2016), applicants from the top 5 refugee producing countries (Syria, Colombia, Afghanistan, Iraq, South Sudan) numbered only 36 in total. Overall, while the number of asylum seekers to our country has increased rapidly in recent years, the majority of applicants do not come from countries that produce many refugees and displaced peoples.” (Immigration Services Agency of Japan, Ministry of Justice 2018, 2)

In the same report, the MOJ also pointed out that most applicants were working aged men, bucking the global trend towards asylum seekers including many women and children. In the 2010s, there was a clear trend showing a rise in applicants from traditional labor migrant-sending countries in South and Southeast Asia following the 2010 decision to allow asylum seekers to work in Japan while awaiting the results of their application (Kalicki 2019). While this fact does not absolve Japan from their international commitments under international refugee law completely, it does at least partly explain the low TPR for 2017.

The second notable trend from Table 2 is the fact that two countries (three if including Ukrainian evacuees) account for the overwhelming number of asylum seekers admitted to Japan: Myanmar and Afghanistan. While the discrepancy between the origin countries of applicants and those granted protection remains intact, this underscores the argument made in the introduction to this piece: the cases of Myanmar and Afghanistan are especially noteworthy to understand the increase in Japan’s TPR as they account for an overwhelming majority (97.4% in 2022) of the country’s recent humanitarian admissions. In addition, the fact that the country admitted more Ukrainian evacuees (2,238)—even though they do not count towards the TPR—than the record-number of asylum seekers admitted (1,914) in 2022 further warrants inclusion of the Ukrainian case within the context of this article.

Diverging Pathways of Entry

While zeroing in on the three cases that will be the focal point of this paper, another important thing to note is that while the Japanese government has granted nationals of Myanmar, Afghanistan, and Ukraine the right to stay in the country based on humanitarian grounds, the legal pathways it chose have diverged (see Table 3). In the case of Myanmar and Afghanistan, Japan utilized the existing legal framework of its asylum policy, though it primarily granted protection based on humanitarian grounds to citizens of Myanmar, while relying on formal refugee status for citizens of Afghanistan. In the case of Ukraine, authorities decided to denominate Ukrainians to be resettled in Japan as “evacuees,” which legally places them outside of formal asylum policy—although the government very much framed their admittance on humanitarian grounds. I will outline the background behind the government’s decision to utilize these diverging pathways in more detail below, as they arose based on the context of each individual case, but simultaneously carry important implications for Japan’s refugee policy moving forward.

Table 3: Pathways to Admittance for Displaced Peoples from Myanmar, Afghanistan, and Ukraine, Total Number Admitted in 2021 and 2022

Based on MOJ data (Immigration Services Agency of Japan, Ministry of Justice 2023a).

Based on MOJ data (Immigration Services Agency of Japan, Ministry of Justice 2023a).

Finally, the Japanese government also granted citizens of all three countries who were already in Japan as the situation in their home country deteriorated the right to stay under the Designated Activities residence status. This was done as an “emergency measure” in order to safeguard those who would have had to return home otherwise due to their previous residence status expiring, and also falls outside the framework of formal asylum policy—although persons granted stay this way can still apply for asylum (Immigration Services Agency of Japan, Ministry of Justice 2023a). These emergency measures are especially relevant in the case of Myanmar, given the comparatively high number of Burmese citizens that were already living in Japan prior to 2021. Starting with the next section, I will outline each case individually, focusing primarily on the geopolitical and strategic background of Japan’s decision to grant asylum and the way it chose to do so.

Click here to read the full article.

*

Note to readers: Please click the share button above. Follow us on Instagram and Twitter and subscribe to our Telegram Channel. Feel free to repost and share widely Global Research articles.

Maximilien Xavier Rehm is a Ph.D. candidate at the Graduate School of Global Studies Doshisha University in Kyoto, Japan. His research focuses on the politics of immigration in Japan, specifically on the policymaking process using an institutionalist approach. He holds a M.A. in International Relations from Ritsumeikan University. Aside from academic publications, Maximilien’s writing has been featured in outlets such as East Asia Forum, The Diplomat and The Japan Times. An updated list of his recent publications can be found here. Contact Info: [email protected]

Featured image is from APJJF

Comment on Global Research Articles on our Facebook page

Become a Member of Global Research

Source link