By Elwin de Groot, Stefan Koopman, and Maartje Wijffelaars of Rabobank (pdf link)

Summary

The European Parliament elections, scheduled for June 6-9, 2024, are expected to carry significant implications for the future of the European Union. This significance primarily arises from the increasing prominence of right-wing parties across Europe, as evidenced by their recent electoral victories and influence in national politics. This election’s outcome does not necessarily preclude the implementation of ambitious plans to overhaul the EU, but it does highlight the risk of either policy stasis or unbalanced decisions.

What’s at stake?

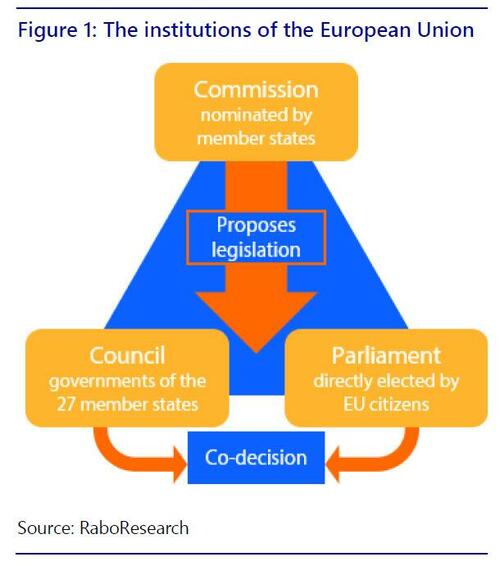

The European Parliament is one of the three key legislative bodies of the European Union (EU), alongside the European Commission and the Council of the European Union.

While the European Commission advocates for the EU’s overall interests and the council represents the governments of member states, the European Parliament upholds the interests of EU citizens. It plays a crucial role in the EU’s legislative and decision-making processes. Despite being perceived as the least influential among the three, it does possess substantial co-legislative authority, including the power to modify and veto legislative proposals in most policy areas. Furthermore, the Lisbon Treaty enhanced its budgetary responsibilities and reinforced its influence over the selection of the European Commission’s president and commissioners. This could prove to be a crucial factor in the months ahead.

Polls indicate the possibility that far-right members of the European Parliament (MEPs) could garner even more support than they won in 2019 (see figure 3). The far right is divided into two groups: the European Conservatives and Reformists (ECR) group and the Identity and Democracy (ID) group. The ECR includes Poland’s Law and Justice party, Italy’s Brothers of Italy, the Sweden Democrats, Spain’s Vox, Belgium’s New Flemish Alliance and France’s Reconquest!. The ID features France’s National Rally, Alternative for Germany, Italy’s League, Belgium’s Flemish Interest, and the Dutch Party for Freedom. There are also parties from the right (e.g., Hungary’s Fidesz) that are not affiliated to any of the European Union's political groups. These sit, alongside parties from the left and center, in the non-inscrit group. Question marks hang in particular over the affiliation of Fidesz, which has a dire record on the rule of law and calls for Ukraine to negotiate peace with Russia. The party has flirted numerous times with the ECR, but for now sits in the new non-inscrits.

A shift toward the right

At first glance, the ECR and ID parties appear to share common ground, but a closer look reveals deep divisions that prevent a united front. Generally speaking, the ECR wants to curb EU powers without disbanding it altogether, while they also are pro-Ukraine, pro-Atlanticism, and pro-NATO. Its MEPs present themselves as Euroskeptics, but they are also somewhat integrated into the EU’s political and institutional framework. Conversely, the ID exhibits a more ambivalent stance vis-àvis Russia, opposes enlargement, is anti-Atlanticist, and is a pariah within EU policy circles.

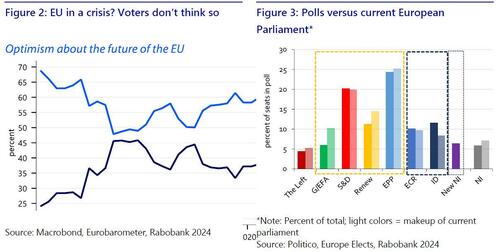

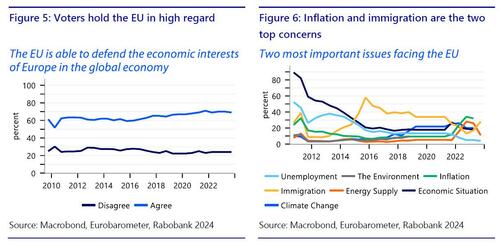

Even though the Eurobarometer survey shows citizens are fairly positive about the EU, polling data indicates the ECR and ID could secure a substantial number of seats in the forthcoming elections. The latest poll averages place them at 73 and 83 seats, respectively, so a combined 156 out of 720 seats. This would surpass the center-left Socialists & Democrats (S&D), who are projected to secure 145 seats, and land not too far from the 175 seats forecast for the center-right European People’s Party (EPP). The liberal Renew Europe and the Greens/EFA are losing support. It is worth noting that MEPs do not necessarily remain put after the election; frequent transfers of lawmakers between groups tend to keep the parliament in flux.

The far right has been largely excluded from power across Europe due to tacit agreements among centrist parties, even as its influence does compel the center right to adopt stricter anti-immigration, anti-trade, and anti-environment stances. It appears another centrist coalition between the EPP and the S&D can be formed, contingent on participation of the Liberals and/or the Greens. A right-wing coalition comprising the EPP and the ECR could also be tried, but this would require additional support from other parties. This looks to be very difficult. A right-wing majority composed of the EPP, ECR, and ID looks to be very unlikely, while the Liberals, the Greens, and the Socialists have ruled out working with both far-right parties.

That said, the right wing’s influence is still poised to shape the dynamics of parliamentary operations and the distribution of high-level roles, potentially complicating the confirmation of the European Commission president and commissioners. The incumbent president, Ursula von der Leyen of the EPP, who seeks a second term, has already engaged with the ECR, further straining her relationship with the S&D. Furthermore, even without a blocking minority or official agreements with other parties, growing support for the far right grants the far right more sway over various policies, including immigration, defense, and environmental issues, by drawing the EPP to the right, away from its alliance with S&D and Renew. Indeed, the European Commission and some mainstream parties in the European Parliament seem to be acknowledging the changing political landscape and are trying to jump on the bandwagon.

A pressing need for change

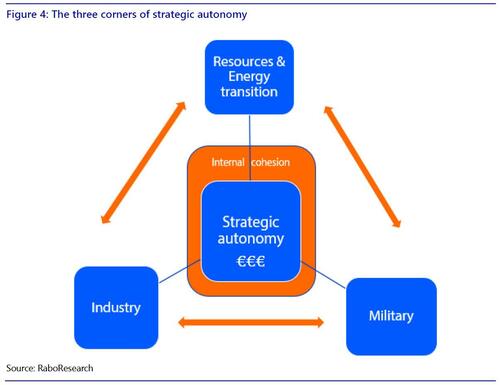

Apart from the internal landscape, rapidly changing geopolitics is also forcing the EU to change course, or to speed up, in certain areas. As we pondered in one of our strategic think pieces, the changing world order forces the EU to put more emphasis on its quest to become strategically autonomous. To summarize that article, we think that Europe’s quest for strategic autonomy hinges on overcoming three intertwined weaknesses: i) energy/raw materials dependency, ii) industrial decline, and iii) military dependence. Meanwhile, preserving social cohesion is a necessary condition to make things work.

Over the past months, EU institutions, politicians and technocrats have released multiple publications and proposals in line with our thinking.

Trump 2.0 sets things in motion

For example, last month, the commission published a paper discussing the economic impact of defense spending, aiming to spark a debate on the most efficient approach. Additionally, an over 700-page report on “state-induced distortions in China’s economy” was published (and met with immediate criticism from China). This illustrates a broader trend of the EU taking a more assertive stance on global economic matters. This is reflected in, for example, the probes into Chinese electric vehicles and wind turbines, and in investigations in international procurement, for example in medical devices.

On one side, this indicates that the EU might align more closely with the US, potentially adopting a tougher stance on China, especially if pressured by a possible new Trump administration. Conversely, Europe also seeks to establish its own distinct strategy. Given its reliance on China for key exports, as well as the strategic resources necessary for the energy transition, a complete severance of EU-China ties seems unlikely. This is underscored by the Letta report, outlined below, which emphasizes the need to maintain the EU’s foundational principles in the face of escalating geopolitical dynamics.

In the event of a future US administration implementing a universal tariff, Europe’s reaction might involve a blend of measured retaliatory tariffs targeting specific American products, coupled with calibrated actions like non-tariff barriers against China. These measures would aim to preserve the overall EU-US relationship, but until Europe achieves a degree of strategic autonomy, it is forced to play a subordinate role.

Letta and Draghi reports setting the “strategic agenda”?

Europe is also strategically bracing itself for a “Trump 2.0 world.” This is becoming evident in the upcoming strategic agenda shaped by European Council’s president and leaders of the member states. The agenda, set for adoption in June 2024, is intended to give guidance to the newly elected parliament and commission and addresses key issues like security, energy, and EU expansion.

In April, former Italian prime minister Enrico Letta added his input to the discussion, advocating for the introduction of a “fifth freedom” to bolster research, innovation, and education. He also stresses the need to develop a single market that has the ability to finance strategic goals and is able to “play big,” but not by undermining its principles of fair competition, cooperation, and solidarity.

Another significant contribution to the strategic agenda, commissioned by EC President Von der Leyen, comes from former European Central Bank president and former Italian PM Mario Draghi. In a speech, Draghi had already emphasized that the European economy is in for a radical overhaul, which requires self-sufficient energy systems, a unified European defense system, and growth in cutting-edge sectors. Or, in three words: climate, defense, and digitalization.

Draghi proposes to integrate further to leverage Europe’s scale, to focus on joint public-private investments in key areas such as defense, energy, climate, and supercomputers. This also requires a capital market union. And, broadly echoing our own conclusions, he emphasizes securing essential resources in critical input materials as well as a skilled workforce.

This again underscores the inevitability of significant costs and tough choices. At this juncture, the opinion of the European electorate becomes pivotal, as it will influence how political parties will address their needs and sentiments.

Will strategic thinking trump immigration and the cost-of-living concerns?

How this would gel with the new parliament?

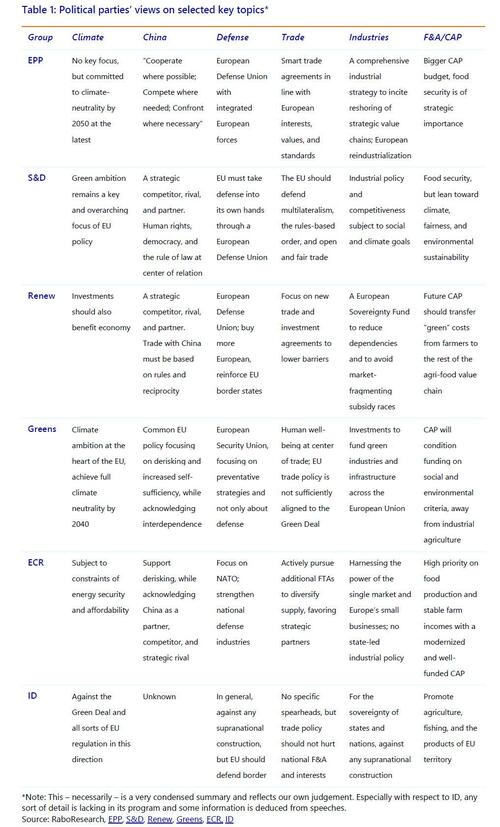

Assuming the formation of another centrist coalition in parliament, it is probable that it will still lean toward the right. In table 1 on the next page, we highlight selected excerpts from election manifestos and recent policy papers on the previously mentioned topics from the five parties we believe will have a significant influence on the coalition talks.

The stance of the EPP will be pivotal. They will need to broker compromises between the positions of the S&D (hawkish on climate/environment/social issues, dovish on EU productive capacity) and those of the ECR (dovish on climate/environment/social issues, hawkish on EU productive capacity, immigration, affordability of energy). This necessitates trade-offs. If those are unattainable, there is the risk of policy stasis on matters where the council is eager to advocate for radical changes.

If we were to venture a guess, the compromises might broadly take the following form:

What are the implications?

In this last section we briefly discuss the potential impact that the political shifts in Europe may have on three specific areas: namely, F&A, the energy transition, and financial markets.

Food and agriculture: A change of tone, but no sea change

In recent years, in line with the Green Deal, discussions have focused on the need to reduce the environmental and climate impact of farming. But due to geopolitical developments and farmer protests reflecting income and business continuity concerns, the commission has changed its tone. Currently, farmers are portrayed as vital for European food self-sufficiency and the sustainable development of rural areas. Greening agriculture is still on the table, but new legislative proposals are subject to more scrutiny on their feasibility, impact on production, and (socioeconomic) impact on rural areas.

With a more right-conservative parliament, this trend is expected to continue. In this new reality, the new parliament has to deal with several questions. To highlight three:

Although a new right-conservative parliament might be less ambitious on reducing the environmental and climate impact of farming, this certainly does not mean European farmers are free from demands. Much of the Green Deal ambitions for agriculture are already laid down in legislation. These include legislation on greenhouse gases, water quality, and biodiversity. Some of this legislation has been in place for decades, but deadlines are nearing and the commission is losing patience with member states not having fulfilled their required efforts and goals.

For instance, the Netherlands, Ireland, and Denmark are phasing out derogations from the Nitrates Directive as water quality hasn’t sufficiently improved. As a consequence, the dairy sectors in these countries are under particular pressure to reduce nutrient losses, which will probably result in a smaller herd size. Moreover, the Water Framework Directive requires water quality to be good in 2027. This increases the need for farmers to reduce nutrient losses and use less plant protection products. Hence, even though new legislation on the latter has been withdrawn, there still is pressure on agriculture to reduce the use of plant protection products.

In short, even with a new right-conservative parliament, farmers still face strict regulations to improve their environmental and climate performance.

Energy transition: Different shades of green

The exiting European Commission already is signaling a different reading of the EU Green Deal. Or at least, it is shifting its accent to parts that were not so high on the agenda back when it was launched, in a 2019, pre-Covid world. The Green Deal Industrial Plan may be hinting at this evolving prioritization, paving the way for stronger state support, more explicitly recognizing the strategic nature of critical raw materials, and initiating the reform of the electricity market design, to ensure the ability to accommodate massive wind and solar generation sources before 2030.

It is clear, and natural, given the geopolitical context, that some points in the original plan may become less prominent. The obvious candidates for diluted efforts, depending on the outcome of the elections, may be the biodiversity policies and those related to the agriculture sector, given their social sensitivity. We also struggle to see a very effective and influential implementation of very socially sensitive regulation, such as the EU ETS II. At least not before “palliative” social measures are put in place both in Brussels and in European capitals.

Meanwhile it is well known that Europe’s greenhouse gas emissions – and the reduction thereof – are becoming less and less definitory in the fate of the global climate, in light of China’s increase and Europe’s decrease. But, it is also crystal clear that the energy transition – or the decarbonization of the energy system – is much more than an environmental effort, as shown by the leading role of China, not known for having a “green agenda” influencing its decision-making. From a more pragmatic and industrial point of view, it has become painfully clear that, if the EU wants to afford some industry and keep or gain some strategic autonomy, it will not be achieved on the shoulders of an energy supply chain relying on European competitors. Not while such providers can afford a much cheaper fossil fuel supply for themselves. An alternative, affordable, and reliable local supply is pivotal for Europe.

Last but not least, there are political factors on the greener side of the balance, such as the strong positioning of Teresa Ribera as officer-to-be of the Green Deal’s next chapter.

With all these elements together, it is not risky to venture that the EU Green Deal may show some brownish areas after the elections, but it may very well grow on steroids in the key areas of renewable and reliable energy supply, simplified strategic permitting, decarbonization of industry, and the deployment of local supply chains.

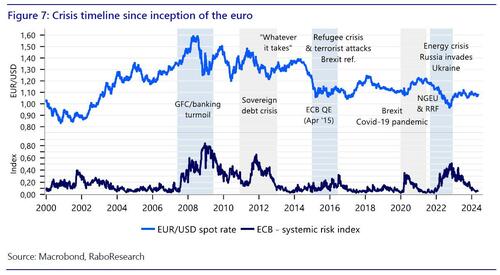

Financial markets: Europe advances with crises not strategic agendas

When gauging the impact of European elections and subsequent policy shifts on financial markets, recall that the direction of the European project has historically been shaped by crises instead of grand strategies. That has proved all too clear in the euro era, marked by the global financial crisis and sovereign debt crisis from 2008 to 2012, the refugee crisis of 2015-16, the

Covid-19 pandemic in 2020-21, and the subsequent significant energy crisis and war in Ukraine.

The unprecedented issuance of joint European debt, for instance, was a response to external shocks – an unplanned but effective move! While Europe’s strategic vulnerabilities may lead to more of these shocks that help the EU fail forward, they also underscore the possibility that strategic plans are sidelined by emergent issues.

A significant breakdown of the European project seems unlikely. The majority of political parties now acknowledge the project’s irreversibility and the necessity for a unified stance on shared external interests. Real Euroskepticism has largely retreated to the political margins. The existence of the euro itself, even as it trades below its purchasing power parity, is not something financial markets are now worried about.

The European Commission and Council have set ambitious goals. In our view, development of a capital markets union could be positive for financial markets, if it were to help unlock new private funding sources, reduce the cost of capital, and enhance competitiveness. This is also on the wish list of most groups in the parliament. Similarly, initiatives to strengthen defense, stimulate innovation, support key industries, and secure supply chains and strategic resources should find enough support. If this indeed increases Europe’s resilience, then this transition could be positive for euro assets.

However, when we juxtapose the possible shape of a compromise in the European Parliament with the commission and council’s ambitions, we could envisage two scenarios that may, at some point, adversely impact euro assets:

Risk of stasis

While the effective response to Covid-19 and the energy crisis highlighted the necessity of EU coordination and joint funding, we could expect some difficult moments on topics such as i) new EU funding sources, ii) the permanence of common funding as a feature of the European toolkit, iii) the need for a permanently larger EU budget, and iv) the need for state aid.

Resistance is likely to come from groups opposed to further integration and the dilution of national competences. Yet even centrist parties like the EPP might object if they perceive this as a threat to prudent budgeting and fiscal sustainability. This could lead to policy stasis and slow down the progress toward Europe’s strategic autonomy. The ambivalent stance on China could also prove a source of stagnation if the EU prioritizes derisking while national governments protect domestic interests. This could obviously weigh on market sentiment at some point.

Risk of unbalanced results

The EU should also avoid unintended demand-supply imbalances. The strategic agenda is costly and adds to demand before it can increase supply. As such, it is potentially inflationary in the transition phase. The impact could be attenuated by prudent budgeting, which requires tough choices, and by the right incentives. A key risk here lies in viewing joint financing, effectively a new layer on top of the existing debt structure, as the “solution” to overcome political hurdles. By this we mean that even when we ignore the condition of fiscal prudence, it is also important that policies steer more actively toward “productive” spending and investment measures rather than just pushing demand or unproductive speculation.

Without such policies, clearly, the other risk is that the same political hurdles force the European Commission and/or Council into compromises that undermine the holistic approach. Sidestepping tough choices or protecting vested interests could lead to an unbalanced package of measures that leads to an unconstrained inflationary impulse. Our analysis suggests the ECB's role is crucial in a holistic strategy. If there is no consensus, we could end up in a situation where the ECB will simply have to pick up the pieces. This is, obviously, not a market-friendly outcome either.

Source link