In the Sajjangarh block of Banswara district, located at the southern tip of Rajasthan, lies a small village called Ghoti ki Todi. Kamladevi Bhagora, a 43-year-old woman from this village, has done something that has become an exemplary inspiration not just for her own village, but for women across many other villages. A mother of three sons, coming from a farming family, this ordinary woman fought for her land, her rights, and her dreams with remarkable courage and she won.

Kamladevi’s childhood was spent in the fields. She learned the art of sowing seeds, growing crops, watering, and harvesting from the very courtyard of her home. From a young age, her hands had a deep bond with the soil. But one thing she had always observed since childhood was this: in the fields, her mother worked just as hard as her father, yet the right to make decisions always remained in the hands of men. What to plant, how much to sell, where to spend money all of this was decided according to the wishes of men. Women only contributed their labor; they had no say in decisions. This social imbalance stayed in young Kamladevi’s eyes like an unanswered question. She did not know that one day she would strive to find the answer to that very question.

Kamladevi’s life began to take a new turn the day she joined Vaagdhara an organization working in the tribal regions of Rajasthan for women’s empowerment, organic agriculture, and community rights. By associating with Vaagdhara, Kamladevi formed Mahila Saksham Samuh (Women’s Empowerment Groups) and Gram Swaraj Samuh (Village Self-Governance Groups) across seven neighboring villages. The Mahila Saksham Samuh brought together 140 women from these seven villages, while the Gram Swaraj Samuh included 140 members both women and men. The goal of these groups was to increase the participation of villagers especially women in gram panchayat affairs. Through these groups, Kamladevi began working on issues such as women’s rights, land ownership, and sustainable agriculture. She became an inspiring leader for the women of these seven villages.

Vaagdhara provided her with in-depth training on land rights, organic sustainable farming, and women’s participation in the Panchayati Raj system. Through capacity-building workshops and field visits, her understanding and vision expanded considerably. She came to understand that until women farmers become aware of their own rights, meaningful change is not possible.

When Kamladevi began talking to the women farmers in her villages about sustainable organic agriculture, she encountered a deep challenge. The women would listen, they would understand — but they would not take the step forward. When Kamladevi thought deeply about it, she realized that these women had no ‘role model’ — no one they could look up to, no one they could identify with. Moving from chemical farming to organic farming was a bold decision, and without a living example, it was difficult for them to make that choice.

Kamladevi recognized the root of this problem and resolved: ‘If I want to show others the way, I must walk it myself first.’ Just as a true leader walks ahead to show the path, she decided to become that example herself.

Kamladevi farms approximately four bighas of land with her family. She first held deep discussions with her family about the matter and shared the long-term benefits of sustainable organic farming. She began practicing sustainable organic agriculture on 3 bighas of land. For this, she did not wait for expensive resources instead, she started with what she had at home. Her household had two cows and eight goats. She prepared organic compost from cow dung. She used traditional bio-pesticides like Dashparni and Neemastra, which are completely natural. In this way, she completely eliminated her dependence on chemical fertilizers and pesticides.

Her main crops were indigenous varieties of maize and tur (pigeon pea). Alongside these, she also grew green vegetables for household use including brinjal, tomatoes, bottle gourd, okra, and onions. Kamladevi always paid special attention to local seed varieties. She would save seeds from her previous harvest to use in the next season. This not only reduced costs but also preserved the purity of the seeds and their adaptability to local weather. This harvest was not just for her it was a living example for the entire village. Women who had earlier listened but not stepped forward could now see with their own eyes that organic farming truly works. Seeing lower costs in the field and superior taste in the produce, the trust of other village women began to awaken.

Kamladevi did not limit her efforts to farming alone. The 8 goats in her household became another source of economic strength. Between 2021 and 2025, she earned a total of ₹1, 02,500 in livelihood income by selling goats. This was a significant achievement, proving that by combining small-scale animal husbandry with farming, a family’s financial condition can be greatly improved. Cow dung became compost; goats became a source of income this integrated farming system brought stability to her life.

Through the Mahila Saksham Samuh and Gram Swaraj Samuh, Kamladevi encouraged women to participate in panchayat meetings. She informed women of their legal rights — the right to a share in land, the right to vote in the panchayat, and the right to benefit from government schemes. Gradually, women’s voices began to grow stronger in these villages. They started attending panchayat meetings and speaking up for themselves.

Seed Banks: The Foundation for the Future

Kamladevi’s foresight did not stop there. She recognized that preserving local seeds not only reduces farming costs but also safeguards our agricultural heritage. She has been working to establish seed banks for local crop varieties in her villages through which farmers can share seeds with one another, local varieties can be preserved, and the compulsion to buy seeds from the market can be eliminated. This initiative may seem small, but its long-term impact is immense. When a community preserves its own seeds, it becomes free from external dependence and ensures its own food security.

A Wave of Inspiration: Light Reaches Over 200 Women

Today, Kamladevi has inspired more than 200 women farmers across 7 villages and has helped them adopt sustainable organic agriculture. These women are now preparing bio-fertilizers in their own fields, using local seeds, and moving away from chemical farming. Surekha Dama, a member of the Mahila Saksham Samuh who was inspired by Kamladevi to take up organic farming, shares her feelings: ‘Adopting organic farming has been very beneficial it has saved our household expenses. All of this is because of Kamla. She boosted my confidence and gave me the opportunity to voice my opinions in decisions. Earlier, we just used to work; now our views are listened to as well.’ Surekha’s words echo the voices of hundreds of women in whose lives Kamladevi has brought light. When one woman empowers herself and lifts others, the entire community transforms.

.

.

The Mark of a True Leader

Kamladevi’s greatest quality is that she has never just spoken words she stepped forward and became the example herself. A true leader is one who first walks the path they wish to show others. Kamladevi did exactly that. Her organic farming, her animal husbandry, her group formation all of these are living proof of her leadership. The training provided by Vaagdhara transformed her thinking, but the courage to bring about change came from within herself. She has proven that a lack of resources cannot block the path of transformation when there is resolve in the heart, the way opens itself.

*

Click the share button below to email/forward this article. Follow us on Instagram and X and subscribe to our Telegram Channel. Feel free to repost Global Research articles with proper attribution.

Vikas Parashram Meshram is a social development practitioner and writer working at the intersection of tribal culture, indigenous knowledge systems, water conservation, and community-led governance. His work is grounded in long-term field engagement with tribal and rural communities in India. He writes on alternative development paradigms, ecological sustainability, and participatory models rooted in traditional practices and lived experiences.

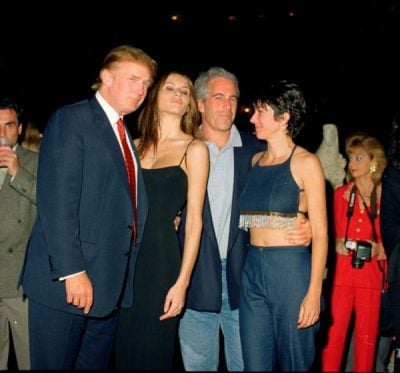

All images in this article are from the author

Global Research is a reader-funded media. We do not accept any funding from corporations or governments. Help us stay afloat. Click the image below to make a one-time or recurring donation.